“Christ is risen from the dead, trampling death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life!”

This blog continues our consideration of Brian Schmisek’s book, Resurrection of the Flesh or Resurrection from the Dead and the development of Christian theology about the resurrection. The previous blog is The Immortal Soul and the Resurrected Body.

The New Testament adhering to the Old Testament anthropology rather than to Platonism speaks of the resurrection from the dead, not of the immortality of the soul. The soul-body dualism enters into Christian thinking as Christianity takes its evangelical message beyond its Jewish origins into the world of Hellenic philosophy. As new adherents are converted to the faith, they begin to ask new questions about how to understand the meaning of the resurrection within the worldview of Hellenism and the Platonic assumptions which were so prevalent in the ancient world. Schmisek writes:

The New Testament adhering to the Old Testament anthropology rather than to Platonism speaks of the resurrection from the dead, not of the immortality of the soul. The soul-body dualism enters into Christian thinking as Christianity takes its evangelical message beyond its Jewish origins into the world of Hellenic philosophy. As new adherents are converted to the faith, they begin to ask new questions about how to understand the meaning of the resurrection within the worldview of Hellenism and the Platonic assumptions which were so prevalent in the ancient world. Schmisek writes:

“we find that neither “resurrection of the flesh” (anastasis sarkos) nor “resurrection of the body” (anastasis sōmatos) appears in the New Testament. Church fathers introduced each of those terms. Instead, in the New Testament one finds the term “resurrection of the dead” (anastasis nekrōn). Or even as some would translate: resurrection “from/out of the dead ones” (ek [tōn] nekrōn).” (Kindle Loc. 1260-63)

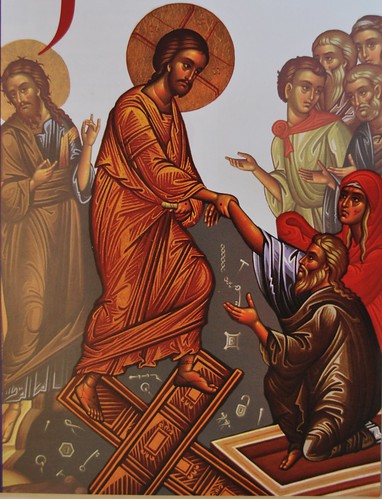

Schmisek rightly notes the New Testament does not use the phrases the resurrection of the flesh or of the body. However, clearly in John’s Gospel in the story of the Apostle Thomas (John 20:19-31), the resurrected Jesus invites Thomas physically to touch His body and to explore His wounds with his fingers and hands. The Orthodox Church has certainly noted this Gospel lesson as teaching the resurrection of the flesh. In Luke’s Gospel (Luke 24:36-43), the risen Christ goes out of his way to show His disciples that He is not some ghostly apparition but that He has returned in bodily form and can be touched and is able to eat solid food. So while the exact phrases about the resurrection of the flesh or of the body do not occur in the New Testament, the ideas for them are clearly there. The Church Fathers simply applied phrases to describe what the Scriptures portray, they did not conjure up the idea of the resurrected flesh or body from thin air.

And, the Christian message was not frozen in the past. The Christians weren’t even proclaiming that “Christ WAS risen…” but rather that “Christ IS risen…” The Christians speaking in the present (in the present tense, as well as whatever contemporary time and place they found themselves in) continued to develop their understanding of the resurrection as well as the appropriate language (vocabularly) for preaching the Good News. The proclamation that Christ is risen from the dead reflects the Old Testament understanding of the human being, the human body and the role of mortality. It is not a proclamation of the immortality of the soul, nor does it accept a soul-body dualism. The person who died is risen – a restoration of the person has occurred, and yet the Risen Christ manifests physical characteristics different than a “normal” human body.

“One sees the development that has taken place up to this point. Paul spoke of the resurrection in terms of “spiritual body.” The Apostolic Fathers stressed that Christ was in the flesh. Since he was in the flesh and rose in the flesh, Christians too will rise in the flesh. Tertullian began to read Paul as one who taught the resurrection of the flesh, even though the term appears nowhere in the Pauline corpus.

‘But when he calls Christ “the last Adam,” recognize from this that he works to establish with all the force of his teaching the resurrection of the flesh, not of the soul.’

It appears that an understanding of a fleshly resurrection arose because Gnostics and, perhaps, other non-Christians were denying the resurrection … ” (Kindle Loc. 393-99)

In a dualistic world in which the body was deemed superfluous if not evil, Christians wanting to emphasize both the incarnation of God in Christ and the goodness of creation itself, began to emphasize more the resurrection of the flesh. This message was understood as being consistent with the Gospel and necessary for refuting dualism. So St. Augustine trying also to affirm the rational and reasonable claims of the resurrection writes:

“Therefore this earthly material, which becomes a corpse when the soul leaves it, will not at the resurrection be so restored that as a result those things which deteriorated and were turned into various things of different kinds and forms, although they do return to the body from which they deteriorated, must necessarily return to the same parts of the body where they originally were. Otherwise, if what is returned to the hair is that which repeated clippings removed, and if what is returned to the nails is that which frequent cuttings have pared away, then to those who think, the image becomes gross and indecent, and for that reason it seems to those who do not believe in the resurrection of the flesh to be hideous. But just as if a statue of some soluble metal were melted by fire, pulverized into dust, or mixed together into a mass, and a craftsman wanted to restore it from the same quantity of matter, it would make no difference with respect to its integrity what particle of matter is returned to which part of the statue, provided that the restored statue resumed the whole of the original. So God, the craftsman, shall restore wondrously and ineffably the flesh and with wonderful and ineffable swiftness from the whole of which it originally consisted. Nor will it be of any concern for its restoration whether hairs return to hairs, and nails to nails, or whether whatever of these that had perished be changed into flesh, and be assigned to other parts of the body, for the providence of the craftsman will take care lest anything be indecent.” (Kindle Loc. 600-611)

Obviously even in the ancient world they wondered about how “scientifically” the resurrection could restore a body that had decomposed to its various elements. The resurrection needed to make sense to all and had to be defended in philosophical (read “scientific” for the ancients) terms. In what manner the elements composing a body were related to the person (mind, soul, self) and how they would all be recomposed in the resurrection were thus essential questions being asked of Christians proclaiming the resurrection. It wasn’t enough for the Christians to preach the Gospel, they had to be able to defend and explain the philosophical and scientific implications of the resurrection to people whose anthropology was different from the assumptions of the biblical texts.

“Augustine claimed that had Adam obeyed God, he would have inherited a spiritual body as a reward for that obedience: ‘however, the first man was from the earth, earthly. He was made into a living being, not into a life-giving spirit, for that was saved for him as a reward for obedience.’ Thus, at the resurrection human beings will not have the body of the first man before sin, because the first man did not have a spiritual body. Augustine cited 1 Corinthians 15:45 to prove that Adam was a living being, while Christ, possessing a spiritual body, was now a life-giving spirit. The spiritual body is a priori, not the body Adam possessed before the Fall. We are not at all to think that in the resurrection we shall have such a body as the first man had before sin; nor is that which is said, ‘As the earthly one, so also those who are earthly,’ to be understood as that which resulted by the commission of sin. For it must not be considered that prior to his sin he had a spiritual body, and that because of the sin it was changed into an animal body. For if this is thought to be the case, then the words of so great a doctor have been given scant attention, who says, ‘If there is an animal body there is also a spiritual, as it is written, The first man Adam was made a living being.’” (Kindle Loc. 563-73)

The proclamation of the Gospel, that Jesus is risen from the dead, thus raised many significant philosophical and scientific questions which the Christians had to be able to answer to convince their fellow citizens of the truth of Jesus Christ. Witnessing to the resurrection was one thing, but the Christians had to convince their pagan neighbors that the resurrection was possible, reasonable and rational. So too, we Christians must be able to speak about the resurrection to people who embrace a modern, scientific understanding of a human, of the body, of the role of death.

“We live in a postmodern era; we know more about the world and how it works than the ancients did. Yet the theological task, like that of our ancient forebears in faith, is to express Christianity in terms the modern culture can understand and find meaningful. Clement did this when he likened resurrection to a phoenix rising from its ashes. Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and the apologists did this when they cast Christianity in terms of Greek philosophy and thus wedded body-soul anthropology with Christian faith. Augustine did this when he expressed Christian faith in terms of neoplatonic philosophy. Aquinas did this when he recast Christian faith in light of Aristotelian philosophy and the science of the thirteenth century. This is the enduring theological task: to cast Christian faith in the language, terms, and culture of the day. … It is not sufficient merely to quote ancient formulas to modern people who do not share the philosophical presuppositions of the ancient world. We must tap into the fundamental beliefs of our forebears in faith and express that faith in language intelligible to our generation.” (Kindle Loc. 2241-52)

“We live in a postmodern era; we know more about the world and how it works than the ancients did. Yet the theological task, like that of our ancient forebears in faith, is to express Christianity in terms the modern culture can understand and find meaningful. Clement did this when he likened resurrection to a phoenix rising from its ashes. Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and the apologists did this when they cast Christianity in terms of Greek philosophy and thus wedded body-soul anthropology with Christian faith. Augustine did this when he expressed Christian faith in terms of neoplatonic philosophy. Aquinas did this when he recast Christian faith in light of Aristotelian philosophy and the science of the thirteenth century. This is the enduring theological task: to cast Christian faith in the language, terms, and culture of the day. … It is not sufficient merely to quote ancient formulas to modern people who do not share the philosophical presuppositions of the ancient world. We must tap into the fundamental beliefs of our forebears in faith and express that faith in language intelligible to our generation.” (Kindle Loc. 2241-52)

Believing Christians today may be so awed by the miracle of the resurrection that they forget others can view these claims not from the point of view of divine intervention, but purely from the point of view of secular materialism or from some other philosophical point of view such as that of the Eastern religions, Hinduism and Buddhism. These people will want to know how our claims make any sense from what is known about the world, or how they help us make sense of this world. And if they can’t make sense of our claims about a resurrection they will not even give Christianity another thought, and might, as our Christian ancestors discovered, rather turn such claims into a topic of derision among the intellectually astute.

“Ultimately, questions about the appearance of the resurrected body do not contribute to the profundity of the resurrection; rather, they drag it into the mire of the ridiculous, as Jerome (d. 420AD) himself experienced:

And to those of us who ask whether the resurrection will exhibit from its former condition hair and teeth, the chest and the stomach, hands and feet, and other joints, then, no longer able to contain themselves and their jollity, they burst out laughing and adding insult to injury they ask if we shall need barbers, and cakes, and doctors, and cobblers, and whether we believe that the genitalia of which sex would rise, whether our [men’s] cheeks would rise rough, while women’s would be soft and whether the bodies would be differentiated based on sex. Because, if we surrender this point, they immediately proceed to female genitalia and everything else in and around the womb. They deny that singular members of the body rise, but the body, which is constituted from members, they say rises.” (Kindle Loc. 2683-91)

Teaching a literal resurrection of the body can raise questions of ridicule as is recorded in the Gospels themselves. So we read in Luke 20:27-38:

There came to him some Sadducees, those who say that there is no resurrection, and they asked him a question, saying, “Teacher, Moses wrote for us that if a man’s brother dies, having a wife but no children, the man must take the wife and raise up children for his brother. Now there were seven brothers; the first took a wife, and died without children; and the second and the third took her, and likewise all seven left no children and died. Afterward the woman also died. In the resurrection, therefore, whose wife will the woman be? For the seven had her as wife.” And Jesus said to them, “The sons of this age marry and are given in marriage; but those who are accounted worthy to attain to that age and to the resurrection from the dead neither marry nor are given in marriage, for they cannot die any more, because they are equal to angels and are sons of God, being sons of the resurrection. But that the dead are raised, even Moses showed, in the passage about the bush, where he calls the Lord the God of Abraham and the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob. Now he is not God of the dead, but of the living; for all live to him.”

On the other hand, a metaphorical interpretation of the resurrection can cause people to doubt its truth and consider it pure worthless speculation. A purely materialistic understanding of the resurrection will be confronted with the atheistic claims of secular materialism.

Christianity has always known it must be bilingual – able to teach and proclaim the message of the Gospel AND to do it within the philosophical and scientific framework which governs the thinking of each different culture and generation. The Church has shown itself able and willing to undertake this evangelical task and has handed on to us Orthodox today that continued task.

Pingback: The Immortal Soul and the Resurrected Body – Fr. Ted's Blog

Pingback: After the New Testament: Proclaiming the Resurrection | Esperinos ☦ Esperinos ☦