David Bentley Hart’s That All Shall Be Saved inspired me to reflect a bit on salvation and how Christ’s coming into the world is good news indeed for all humankind. His book brought to the forefront of my thinking the many reasons I joyfully embrace Christianity as my faith and experience of God. This is the 5th and final post in this blog series which is looking at ideas from his book which have been an anchor to my faith. The previous post is: Is Free Will the Curse?

David Bentley Hart’s That All Shall Be Saved inspired me to reflect a bit on salvation and how Christ’s coming into the world is good news indeed for all humankind. His book brought to the forefront of my thinking the many reasons I joyfully embrace Christianity as my faith and experience of God. This is the 5th and final post in this blog series which is looking at ideas from his book which have been an anchor to my faith. The previous post is: Is Free Will the Curse?

The Gospel is and is meant to be good news for all of us who inhabit planet earth and struggle in life, who have to cope with evil and the effect of sin on our existence here. And while the good news promises us salvation, it does not promise us life on earth will be easy, without suffering or temptation or death. We are to be of good cheer because Christ has overcome all of these aspects of the world, and so they are proven to be limited, circumscribed, in their power.

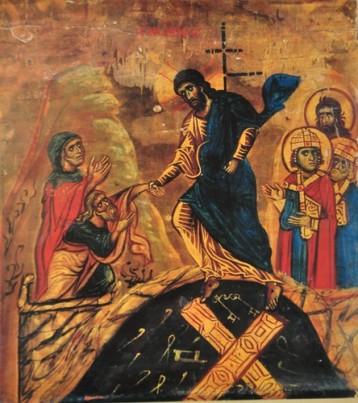

In its dawn, the gospel was a proclamation principally of a divine victory that had been won over death and sin, and over the spiritual powers of rebellion against God that dwell on high, and here below, and under the earth. It announced itself truly as the “good tidings” of a campaign of divine rescue on the part of a loving God, who by the sending of his Son into the world, and even into the kingdom of death, had liberated his creatures from slavery to a false and merciless master, and had opened a way into the Kingdom of Heaven, in which all of creation would be glorified by the direct presence of God.

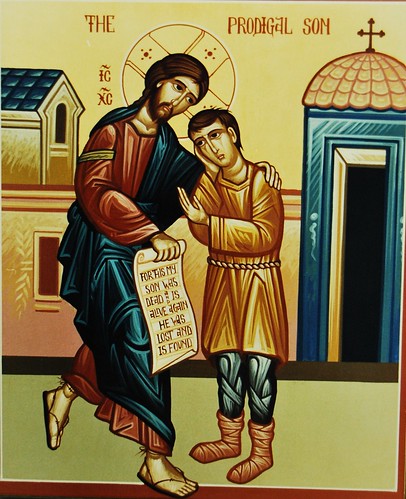

It was an announcement that came wrapped in all the religious and prophetic and eschatological imagery of its time and place, and armored in the whole metaphorical panoply of late antique religion, but with far less of the background and far fewer of the details filled in than later Christians would have found tolerable. It was, above all, a joyous proclamation, and a call to a lost people to find their true home at last, in their Father’s house. It did not initially make its appeal to human hearts by forcing them to revert to some childish or bestial cruelty latent in their natures; rather, it sought to awaken them to a new form of life, one whose premise was charity. Nor was it a religion offering only a psychological salve for individual anxieties regarding personal salvation. It was a summons to a new and corporate way of life, salvation by entry into a community of love. Hope in heaven and fear of hell were ever present, but also sublimely inchoate, and susceptible of elaboration in any number of conceptual shapes. Nothing as yet was fixed except the certainty that Jesus was now Lord over all things, and would ultimately yield all things up to the Father so that God might be all in all. (Hart, That All Shall Be Saved, Kindle Location 2790-2803)

When the Lord Jesus came eating and drinking with sinners was He not enacting the very thing He proclaimed in His parables – that those invited to the wedding banquet did not wish to attend and so the banquet had been opened to all – undesirable people were invited, even compelled to come in and join the banquet even though they were undesireable? Did not the Jesus’ own lifestyle and actions, especially His table fellowship, announce that the Kingdom of Heaven had come, that God had reconciled the world to Himself? Yet, we see already in the New Testament a rejection of this reconciliation between God and God’s creation. Pharisees, among others, rejected Christ’s message and condemn Him for His table fellowship with sinners. A concern for judgment of sinners and unbelievers comes to the forefront of thinking as Christians see people not only rejecting the Gospel but also persecuting believers. Being forgiven by God, reconciled to God, united to divinity was not enough good news for believers – they thirsted for triumph over enemies and retribution for sinners. Rather than sorrowing that everyone did not embrace salvation, believers began persecuting those who didn’t believe. The values of the Kingdom of Heaven were replaced by the values of worldly kingdoms.

However, the Church never lost sight of its message. The Gospel shone through the centuries to those who would hear it. St. Leo the Great (d. 461AD) writing in the 5th Century about the Nativity of Christ still captures the joyous message of salvation for everyone:

“Our Saviour, dearly beloved, is born today; rejoice! For it is not fitting that we give any place to sadness when Life is born, the Life which, consuming the fear of death, has filled us with joy because of the eternity He promises. No one is excluded from this gladness. One reason for joy is common to all, since Our Lord, the destroyer of sin and death, as he found no one free from sin, came to deliver us all. The saint is to exult, for he is nearing his palm. The sinner is to rejoice, for he is invited to forgiveness. The pagan is to take courage, for he is called to life…

And so, dearly beloved, we are to give thanks to God the Father, through His Son, in the Holy Spirit, to Him who, in the abundant mercy with which He has loved us, has had pity on us, and ‘when we were dead in our sins, has brought us to life together with Christ’, so that we may be in Him a new creature, a new work. Let us, then, take off the old man with his works, and become partakers in the generation of Christ, renouncing the works of the flesh. O Christian, realize your dignity: you are associated with the divine nature, do not turn back to your past base condition by a degenerate way of life. Remember that you have been rescued from the power of darkness, you have been transported into the light and the kingdom of God. By the sacrament of Baptism, you have been made the temple of the Holy Spirit. Do not make such a guest take flight by perverse actions nor submit yourself again to the devil’s slavery, for you have been redeemed by the blood of Christ, for He will judge you in truth, He who has redeemed you in mercy, He who lives and reigns with the Father and the Holy Spirit for ever and ever. Amen.” (THE SPIRITUALITY OF THE NEW TESTAMENT & THE FATHERS by Louis Bouyer, p 530)

St. Symeon the New Theologian (d. 1022AD) writing five centuries after St Leo says:

“… He Himself, Who is able to do all things and is beneficent, undertook to accomplish this work through Himself. For the man whom He had made by His own invisible hands according to His image and likeness He willed to raise up again, not be means of another but by Himself, so that indeed he might the more greatly honor and glorify our race by His being likened to us in every respect and become our equal by taking on our human condition. O what unspeakable love for mankind! The goodness of it! That not only did He not punish us transgressors and sinners, but that He Himself accepted becoming such as we had become by reason of the Fall: corruptible man born of corruptible man, mortal born of a mortal, sin of him who had sinned, He Who is incorruptible and immortal and sinless. He appeared in the world only in His deified flesh, and not in His naked divinity. Why? Because He did not, as He says Himself in His Gospels, wish to judge the world but to save it.” ( ON THE MYSTICAL LIFE Vol 1, pp 144-145)

Christ did not become incarnate in order to condemn humans, but, rather, to save them. God became human so that we humans might become god. If He wanted to condemn sinners, He didn’t need to die on the cross. That death is God’s love and will for humanity – God uniting Himself to humanity, not spurning humanity because it is fallen and sinful. Why senselessly be tortured for humanity if your goal is punishment for sinners in the first place? The life, death and resurrection of Christ are God’s continued effort to bring about God’s own plan: to unite heaven and earth, to reconcile humanity to God so that we humans might share in the divine love and life.

Writing 900 years after St Symeon, Archimandrite Sophrony building upon the words of St Silouan the Athonite discusses the struggle with evil humanity has faced through the centuries:

“The history of the Orthodox Church, past and present, right up to our own day reveals frequent instances of a leaning towards the idea of physical combat against evil, though fortunately confined to individual prelates or ecclesiastical groups. The Orthodox Church herself has not only declined to bless or to impose these measures but has always followed in the steps of the crucified Christ, Who took upon Himself the burden of the sins of the world. The Staretz was profoundly and very precisely aware that only good can defeat evil – that using force simply means substituting one sort of violence for another. We discussed this many a time. He would remark, ‘The Gospel makes it plain that when the Samaritans did not wish to receive Christ, the disciples James and John wanted to bring down fire from heaven, to consume them, but the Lord rebuked them and said, “Ye know not what manner of spirit ye are of . . . I am come not to destroy men’s lives, but to save them”.’ And we, too, must have this one thought – that all should be saved.” (ST. SILOUAN THE ATHONITE, p 226)

David Bentley Hart is in good company as he argues the purpose of God’s incarnation in Christ, His death and resurrection all were done for the salvation of the world not for condemning sinners to hell. As previously noted, a message of universal salvation does not change the struggle which believers face in the world, does not deny that evil is real, does not take away the suffering undergone in this world by innocent people. It does bring the Gospel to the forefront of the Christian message and says “God is love” is not an idea that can be negotiated or altered. Rather it becomes the key to interpreting all of Scripture. God’s purpose in creating the cosmos is to bring all things into communion with God. This is God’s plan, unaltered by human sinfulness, which is being realized from creation to salvation in Christ to the kingdom of God. God is both Creator and Savior because God’s will is that we should be united to God. As Hart says:

… between God’s antecedent and consequent decrees: between, that is, his original will for a creation unmarred by sin (“Plan A,” so to speak) and his will for creation in light of the fall of humanity (“Plan B”). And it has usually been assumed that, whereas the former would have encompassed all of creation in a single good end, the latter merely provides for the rescue of only a tragically or arbitrarily select portion of the race. But why? Perhaps the only difference, really, between these antecedent and consequent divine decrees (assuming that such a distinction is worth making at all) is the manner by which God accomplishes the one thing he intends for creation from everlasting. Theologians and catechists may have concluded that God would ideally have willed only one purpose but must in practical terms now will two; but logic gives us no reason to think so. Neither does scripture (at least, not when correctly read). After all, “our savior God,” as 1 Timothy 2:4 says, “intends all human beings to be saved and to come to a full knowledge of truth.” (Hart, That All Shall Be Saved, Kindle Location

I have gathered all the posts from my blog series reflecting on David Bentley Hart’s book, THAT ALL SHALL BE SAVED, into one PDF for those who prefer to read it as a document rather than have to navigate through several posts. You can find that document at

I have gathered all the posts from my blog series reflecting on David Bentley Hart’s book, THAT ALL SHALL BE SAVED, into one PDF for those who prefer to read it as a document rather than have to navigate through several posts. You can find that document at

David Bentley Hart in his book,

David Bentley Hart in his book,