But Jesus called them to him, saying, “Let the children come to me, and do not hinder them; for to such belongs the kingdom of God. Truly, I say to you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it.” (Luke 18:16-17)

Jesus said, “Truly, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” (Matthew 18:3)

While Jesus taught that we have to become like a child to enter the Kingdom of God, through history theological reflection tended not to see the Kingdom from a child’s point of view. Theology made ideas of the Kingdom ever more complex. Even the Liturgy which is to reflect the Kingdom was not understood from the point of view of the child but became increasingly complex with layers of meaning that no child could even see let alone understand. The Liturgy seems not to have been developed with the child in mind, and today many people do not appreciate children in the Liturgy because they are noisy, distracting, disruptive while they want an experience free of childlike behavior. And yet we cannot enter that Kingdom unless we become like a child for the Kingdom and the Liturgy which reflects it are not the constructs of theologians, scholars, mystics and the highly educated experts, but are the revelation of and from God for those who can be children.

The late great liturgical scholar Robert Taft summarized the Orthodox Liturgy this way:

“In the cosmic or hierarchical scheme, church and ritual are an image of the present age of the Church, in which divine grace is mediated to those in the world (nave) from the divine abode (sanctuary) and its heavenly worship (the liturgy enacted there), which in turn images forth its future consummation (eschatological), when we shall enter that abode in Glory. Symeon of Thessalonika (d. 1429), last of the classic Byzantine mystagogues, has synthesized this vision in chapter 131 of his treatise ON THE HOLY TEMPLE:

“In the cosmic or hierarchical scheme, church and ritual are an image of the present age of the Church, in which divine grace is mediated to those in the world (nave) from the divine abode (sanctuary) and its heavenly worship (the liturgy enacted there), which in turn images forth its future consummation (eschatological), when we shall enter that abode in Glory. Symeon of Thessalonika (d. 1429), last of the classic Byzantine mystagogues, has synthesized this vision in chapter 131 of his treatise ON THE HOLY TEMPLE:

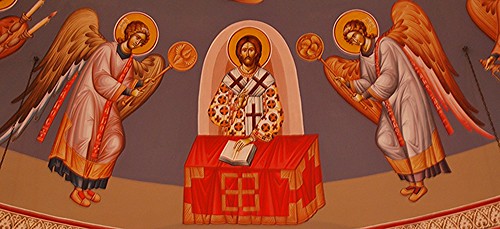

The church, is the house of God, is an image of the whole world, for God is every where and above everything. . . . The sanctuary is a symbol of the higher and super-celestial spheres, where the throne of God and his dwelling place are said to be. it is this throne which the altar represents. … The bishop represents Christ, the church [nave] represents the visible world. . . .

I mention the apostles with the angels, bishops and priests, because there is only one Church, above and below, since God came down and lived among us, doing what he was sent to do on our behalf. And it is a work which is one, as is our Lord’s sacrifice, communion, and contemplation. And it is carried out both above and here below, but with this difference: above it is done without any veils or symbols, butt here it is accomplished through symbols. . . .

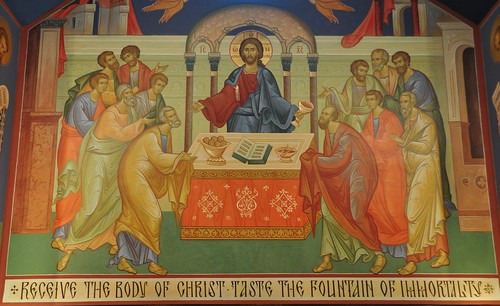

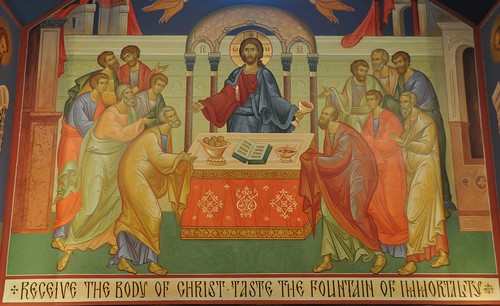

In the economic on anamnetic scheme, the sanctuary with its altar is at once: the Holy of Holies of the tabernacle decreed by Moses; the Cenacle of the Last Supper; Golgotha of the crucifixion; and the Holy Sepulchre of the resurrection, from which the sacred gifts of the Risen Lord — His Word and His body and blood — issue forth to illumine the sin-darkened world. . . .

In the economic on anamnetic scheme, the sanctuary with its altar is at once: the Holy of Holies of the tabernacle decreed by Moses; the Cenacle of the Last Supper; Golgotha of the crucifixion; and the Holy Sepulchre of the resurrection, from which the sacred gifts of the Risen Lord — His Word and His body and blood — issue forth to illumine the sin-darkened world. . . .

In the iconography and liturgy of the church, this twofold vision assumes visible and dynamic form. From the central dome the image of the Pantocrator dominates the whole scheme, giving unity to the hierarchical and economic themes. The movement of the hierarchical theme is vertical: ascending from the present, worshiping community assembled in the nave, up through the ranks of the saints, prophets, patriarchs, and apostles, to the Lord in the heavens attended by the angelic choirs. The economic or ‘salvation-history’ system, extending outwards and upwards from the sanctuary, is united both artistically and theologically with the hierarchical. ” (THE BYZANTINE RITE: A SHORT HISTORY, pp 69-70)

In the iconography and liturgy of the church, this twofold vision assumes visible and dynamic form. From the central dome the image of the Pantocrator dominates the whole scheme, giving unity to the hierarchical and economic themes. The movement of the hierarchical theme is vertical: ascending from the present, worshiping community assembled in the nave, up through the ranks of the saints, prophets, patriarchs, and apostles, to the Lord in the heavens attended by the angelic choirs. The economic or ‘salvation-history’ system, extending outwards and upwards from the sanctuary, is united both artistically and theologically with the hierarchical. ” (THE BYZANTINE RITE: A SHORT HISTORY, pp 69-70)

The Liturgy and the Church are about ranks of bishops, apostles, angels, priests, saints, prophets and patriarchs. What is missing? Children. We cannot enter the Kingdom without them or without being one of them. We don’t have to have a seminary degree to understand the Liturgy. We need the eyes of a child. If the received Tradition forgets that, it has forgotten a key to the Kingdom. We can do the Liturgy perfectly rubrically correct, according to the Typikon, with every ritual required. We still need to have the heart of a child to enter the Kingdom.

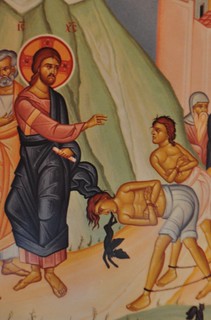

It also is interesting that the received Tradition turned to and returned to the Old Testament for its liturgical meaning, rites and symbols rather than exploring themes suggested by the Gospel. In the Old Testament, we understand, everything was in shadows and symbols: “For since the law has but a shadow of the good things to come instead of the true form of these realities…” (Hebrews 10:1) Christ came and revealed the Light opening Paradise to us, opening our hearts and minds and eyes to see clearly no longer in shadows: “the people who sat in darkness have seen a great light, and for those who sat in the region and shadow of death light has dawned.” (Matthew 4:16) But now according to Taft’s description it is the nave of the church and the non-clergy who live in the world of symbols (the shadowy world of the Old Testament!). It is all that the Church permits for the non-clergy. Behind the icon wall, reserved for the clergy is the Kingdom opened. The Gospel, however, proclaims that we no longer sit in darkness or in shadows for the Light has come. There is another effect of this return to the shadows of the Old Testament – the hierarchy serves to further distance the Savior from the people He saved! It is moving away from Christ who ended all of the dividing walls and opened Paradise to all.

For he is our peace, who has made us both one, and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility, by abolishing in his flesh the law of commandments and ordinances, that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us both to God in one body through the cross, thereby bringing the hostility to an end. And he came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near; for through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father. So then you are no longer strangers and sojourners, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone, in whom the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Lord; in whom you also are built into it for a dwelling place of God in the Spirit. (Ephesians 2:14-22)