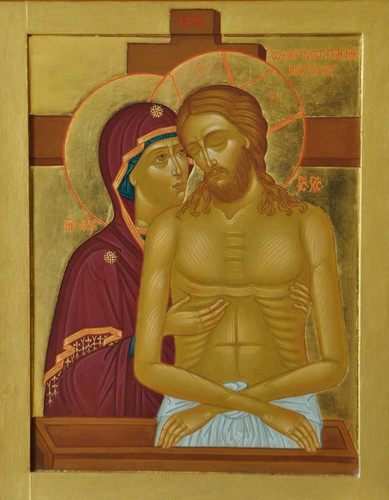

“…in the Bible to bless God is not a “religious” or “cultic” act, but the very way of life. …All rational, spiritual and other qualities of man, distinguishing him from other creatures, have their focus and ultimate fulfillment in this capacity to bless God, to know, so to speak, the meaning of the thirst and hunger that constitutes his life. “Homo sapiens”, “homo faber”…yes, but first of all, “homo adorans”. The first and basic definition of man is that he is the priest. He stands at the center of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God…” (Fr. Alexander Schmemann, For The Life of the World)

“…in the Bible to bless God is not a “religious” or “cultic” act, but the very way of life. …All rational, spiritual and other qualities of man, distinguishing him from other creatures, have their focus and ultimate fulfillment in this capacity to bless God, to know, so to speak, the meaning of the thirst and hunger that constitutes his life. “Homo sapiens”, “homo faber”…yes, but first of all, “homo adorans”. The first and basic definition of man is that he is the priest. He stands at the center of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God…” (Fr. Alexander Schmemann, For The Life of the World)

Fr Schmemann saw the human as basically a worshiping creature. Yes, we are ingenious at fabricating things, we are sentient and capable of wisdom. But for Schmemann the human was created by God to be a priest, to worship the Lord and that is partially what we lost when we humans decided we don’t need God to know our universe. As soon as we desired to approach the cosmos in a role other than as priest in service of God, when we stopped seeing creation as a means to our maintaining our relationship with God, we lost our unique role as humans in the cosmos and lost our communion with our Creator.

St. Basil the Great saw humans as ‘homo legitur‘ – the literary beings – the ones, as theologian Stephen M. Hildebrand notes in his biography of the Saint, created by God to be able to read not only the scriptures but the cosmos itself. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins writes this ability to read is what sets humans apart as a species: “Our ability to understand the universe and our position in it is one of the glories of the human species. Our ability to link mind to mind by language, and especially to transmit our thoughts across the centuries is another. Science and literature, then, are the two achievements of Homo sapiens that most convincingly justify the specific name” (THE OXFORD BOOK OF MODERN SCIENCE WRITING, p 3). Modern science agrees with St Basil that we are gifted to read. However, a difference between modern science and St Basil would be that Basil believed God gave us two sets of scripture – the Bible and creation, both written to reveal God to us. We need to learn to read both while modern science only wants to focus on the empirical cosmos which it does not see as revealing divinity to us. Hildebrand writes:

“Basil sees man as a reader, but a reader must have a text. Man’s texts, for Basil, are principally two, the Scriptures and the whole of creation, including the human body. The author of man’s two books is God himself. One important implication here is that both the Scriptures and creation, being texts, are full of meaning and significance. The posture that the French poet Paul Claudel took before reality expresses well St. Basil’s too. Claudel in front of a piece of reality—a flower, a mountain, a woman—always felt the need to ask, “Qu’est-ce que ça veut dire?”‘ We might typically translate this as ‘What does it mean?’ but literally it is rendered ‘What does it want to say?’ For Basil, the Scriptures and the world want to say something, or God wants to say something through them.

“Basil sees man as a reader, but a reader must have a text. Man’s texts, for Basil, are principally two, the Scriptures and the whole of creation, including the human body. The author of man’s two books is God himself. One important implication here is that both the Scriptures and creation, being texts, are full of meaning and significance. The posture that the French poet Paul Claudel took before reality expresses well St. Basil’s too. Claudel in front of a piece of reality—a flower, a mountain, a woman—always felt the need to ask, “Qu’est-ce que ça veut dire?”‘ We might typically translate this as ‘What does it mean?’ but literally it is rendered ‘What does it want to say?’ For Basil, the Scriptures and the world want to say something, or God wants to say something through them.

So man is the reader, and creation and the Scriptures are the texts, the books. Basil tells his flock, ‘This whole world is as it were a book that proclaims the glory of God, announcing through itself the hidden and invisible greatness of God to you who have a mind for the apprehension of truth‘ (Hex. 11.4; 51). The text, whether creation, the Scriptures, or the human body, calls for a response from the reader.” (Basil of Caesarea, Kindle Loc 657-667)

Basil believed the cosmos, creation, including the human body were a text to be read by humans to understand what God has done, is doing, is going to do. In every sense of the word, Basil looked beyond the literal to find the meaning and for him the meaning always had to do with discovering the Creator through God’s activity in the cosmos. “Glory to You [O Lord] spreading out before me heaven and earth, like the pages in a book of eternal wisdom” (from the Akathist, “Glory to God for All Things”).

I would suggest that St Basil would have been impressed with exactly how much modern science and technology has been able to read from the text of creation including the human body. Just think about all the things we read in drawing blood samples from people or through pathology, chemical analysis, and especially now through DNA which is literally a language that has been recording all that God has been doing in and through humans for as long as humanity has been on the planet and even in the millions of years before that. “In the beginning was the word. The word was not DNA. That came afterwards, when life was already established … But DNA contains a record of the word, faithfully transmitted through all subsequent aeons to the astonishing present” (Matt Ridley quoted in THE OXFORD BOOK OF MODERN SCIENCE WRITING, p 40).

I would suggest that St Basil would have been impressed with exactly how much modern science and technology has been able to read from the text of creation including the human body. Just think about all the things we read in drawing blood samples from people or through pathology, chemical analysis, and especially now through DNA which is literally a language that has been recording all that God has been doing in and through humans for as long as humanity has been on the planet and even in the millions of years before that. “In the beginning was the word. The word was not DNA. That came afterwards, when life was already established … But DNA contains a record of the word, faithfully transmitted through all subsequent aeons to the astonishing present” (Matt Ridley quoted in THE OXFORD BOOK OF MODERN SCIENCE WRITING, p 40).

Just think about ways we read creation today: paleontology, archaeology, radio waves, molecular structures, laws of physics, history, anthropology, biological evolution, quantum mechanics, chemical structures and signatures, mathematical equations, binary code, the remnants of the Big Bang, just to name a few. Creation has been recording all that God is doing from the beginning, and we are just beginning to learn to read the text which is the cosmos and to understand God’s creation and God’s activity from the beginning of the universe. God has His hand in creating the cosmos and that cosmos is the record of what God was and is writing. God’s narrative is God’s creation just as Scripture is – God’s word for those who could read to comprehend what God is willing to reveal.

We can read today so much more from the cosmos and about creation than St Basil ever imagined was possible (as well as countless things he couldn’t imagine at all). As we sing in the Akathist “Glory to God for All Things”: “The breath of Your Holy Spirit inspires artists, poets, scientists. The power of Your supreme knowledge makes them prophets and interpreters of Your laws, who reveal the depths of Your creative wisdom. Their works speak unwittingly of You. How great are You in Your creation! How great are You in man!”

Of course, just like in scriptural interpretation there is the danger of reading what we believe into the text rather than seeing what the text reveals. Eisegesis instead of exegesis is a risk for scientists as it is for biblical scholars.

We are the creatures who have learned not only to read, but also to write, to create literature. This is part of what Dawkins says sets humans apart. But in creating literature, we also are not only using our reading skills, we are participating in creation and in the creative process. Chemist Peter Atkins who says all creation is moving toward chaos and collapse notes that literature, as well as music and architecture really are ways in which we slow down nature’s slide into chaos. “The emergence of consciousness, like the unfolding of a leaf, relies upon restraint. Richness, the richness of the perceived world and the richness of the imagined worlds of literature and art – the human spirit- is the consequence of controlled, not precipitate, collapse” (quoted in THE OXFORD BOOK OF MODERN SCIENCE WRITING, p 16).

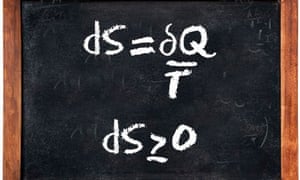

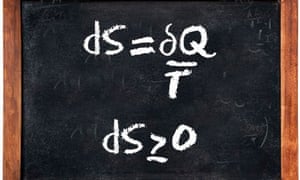

The Genesis creation account has God working against chaos, against entropy, to create [Greek: Poetry] order and bring life into existence. This is a miracle in the midst of the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics. Humans have an ability as God does to bring restraint to the universal move toward entropy. Our ability to read and write are part of our creative abilities which put restraint, even if only temporarily on the slide to chaos. God as the original writer or poet of creation gives to us what we can read – God brings restraint to entropy. We humans can share in that creativity by exhibiting restraint! And when we are truly creative, we put restraint on entropy as Atkins noted. ‘Art’ that yields chaos is simply doing what the cosmos does naturally -move toward entropy which in the end is not art at all. True human genius is restraining to entropy and controlled.

Hildebrand continues:

“As Basil says about Genesis 1:26, ‘We have, on the one hand, you see, what looks, in its form, like a story, but is, on the other hand, at the level of power, a theology’ (Hex. 10.4). God, then, is not concerned merely to communicate so much information, even useful information, about himself or about us. The Scriptures are not just informative, but, if you will, performative, and here the action that God wishes us to perform is the worship of him as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. As a reader, man is constantly called to relate to God and to his own salvation what he finds in the two great books, Scripture and creation, that have been given to him. This is why Basil is never interested in mere history or mere observation.” (Basil of Caesarea, Kindle Loc 673-678)

Science will only be interested in the informative part of creation, but believers are called to the performative part – knowing the truth, how are we to behave? This is where St Basil is not so much interested in history or the ‘facts’ as he is in what does it mean, especially in our understanding of God and God’s will. Basil sees Genesis as story but as a narrative with a message: the revelation of God also known as theology. It is the message which we ultimately want to know. To turn Genesis into science or facts or to reduce it to history is to look at creation through the eyes of science rather than the eyes of faith. Scripture is to open the eyes of our heart to the depths of meaning which God is revealing to us. The study of creation can have the same purpose which is why Christians should pay attention to nature and science as St Basil recommended.

“…in the Bible to bless God is not a “religious” or “cultic” act, but the very way of life. …All rational, spiritual and other qualities of man, distinguishing him from other creatures, have their focus and ultimate fulfillment in this capacity to bless God, to know, so to speak, the meaning of the thirst and hunger that constitutes his life. “Homo sapiens”, “homo faber”…yes, but first of all, “homo adorans”. The first and basic definition of man is that he is the priest. He stands at the center of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God…” (

“…in the Bible to bless God is not a “religious” or “cultic” act, but the very way of life. …All rational, spiritual and other qualities of man, distinguishing him from other creatures, have their focus and ultimate fulfillment in this capacity to bless God, to know, so to speak, the meaning of the thirst and hunger that constitutes his life. “Homo sapiens”, “homo faber”…yes, but first of all, “homo adorans”. The first and basic definition of man is that he is the priest. He stands at the center of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God…” ( “

“

This is the third post in his blog series exploring

This is the third post in his blog series exploring

whose empire was expanding, sent sailors to navigate the seas and explore the world. They brought back to China all kinds of exotic animals from distant lands. They also spoke of the many different peoples they encountered in the world: the varied races, languages and customs they discovered in their journeys. The book mentions the Chinese also heard and believed there were even stranger people living in distant and mysterious lands – including dog-headed humans.

whose empire was expanding, sent sailors to navigate the seas and explore the world. They brought back to China all kinds of exotic animals from distant lands. They also spoke of the many different peoples they encountered in the world: the varied races, languages and customs they discovered in their journeys. The book mentions the Chinese also heard and believed there were even stranger people living in distant and mysterious lands – including dog-headed humans.