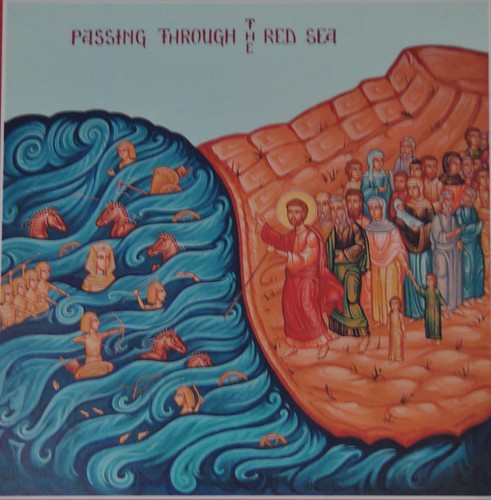

When I read John McGuckin’s chapter, “The Christian Sense of the Desert,” in his book Illumined by the Spirit, I immediately saw its connection to Great Lent and also how the desert experience is a description of Great Lent. It helps contextualize what we are called to experience in our Lenten sojourn. We come to realize one way to understand the fasting, abstinence and self-denial – it is our own spiritual walk into the desert, related to what Israel undertook when God called Israel out of Egypt and into the desert where they would see God’s face and glory as well as look into the face of death.

When I read John McGuckin’s chapter, “The Christian Sense of the Desert,” in his book Illumined by the Spirit, I immediately saw its connection to Great Lent and also how the desert experience is a description of Great Lent. It helps contextualize what we are called to experience in our Lenten sojourn. We come to realize one way to understand the fasting, abstinence and self-denial – it is our own spiritual walk into the desert, related to what Israel undertook when God called Israel out of Egypt and into the desert where they would see God’s face and glory as well as look into the face of death.

The article begins with a poem by Edward Dorn:

’The first law of the desert

to which animal life of every kind

pays allegiance

is endurance and abstinence.’

Endurance and abstinence – two very apt descriptions for what we experience on our Lenten sojourn. Even if we only keep Great Lent minimally, we do experience its length and have to endure. And if we keep any kind of fasting – whether from food, entertainment, sex, the internet – we are practicing abstinence from some things. We come to realize that Great Lent takes us out into the desert and says, “your survival is dependent on your willingness to deny yourself.” If you feel you have to indulge yourself, you won’t survive in the desert. As modern people we may abandon the desert, the fast, but in doing that we learn how much we really love the world rather than God. We find that we don’t even want to rely on God or to live on the Word of God, we really want to have the things of the world that we crave rather than the Creator of this world. And we see this in the smallest of things – a piece of cheese, a hamburger, a little downtime in front of the TV or the computer. “Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world— the desires of the flesh and the desires of the eyes and pride of life —is not from the Father but is from the world. And the world is passing away along with its desires, but whoever does the will of God abides forever” (1 John 2:15-17).

McGuckin goes on to write:

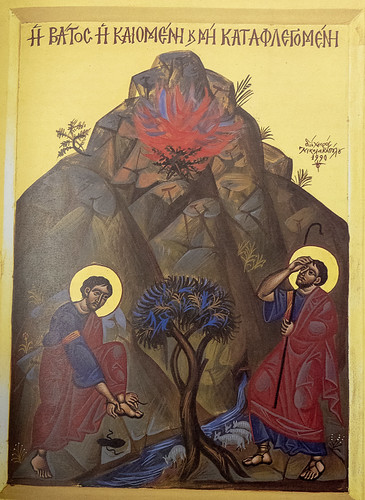

“The ancient world generally saw the desert as a cursed place. Its barrenness, its stark and unremitting hostility to all life forms, especially human, was a primal symbol of the fearsome anger and power of God who seemed to have withdrawn the vitality of life from such a place even as he had withdrawn water, that deep symbol of the graciousness of the Holy Spirit. Christians, reflecting on the Scriptures, saw the desert in a symbolically different way as the quintessential zone of pilgrimage to the promised land, and gave it a new significance: comparable to the reference to the wilderness in the prophet Hosea, who called to the Israelites of his time to return to the Lord God with love and zeal, citing the desert years of wandering as a time when Israel still felt like a lover in the presence of God, before faithlessness and tedium had turned the marital relationship sour.

Hosea’s text, though not often cited explicitly in the early Church, in many ways sums up the special Christian sensibility of what would develop as ‘desert spirituality’ – characterized by an energy of repentance, a turning back (Heb: shub, Gk: metanoia), a return to simplicity which casts off distractions, in order to rediscover the heart of one’s relationship with God. Hosea puts this call to repentance into the mouth of God himself musing about his love affair with Israel and his plans to revive it:

“Therefore, behold, I will allure her, and bring her into the wilderness, and speak tenderly to her. And there I will give her her vineyards, and make the Valley of Achor a door of hope. And there she shall answer as in the days of her youth, as at the time when she came out of the land of Egypt. “And in that day, says the LORD, you will call me, ‘My husband,’ and no longer will you call me, ‘My Baal.’ (Hosea 2:14-16)

This movement towards the desert not so much as a holy place, but more as the symbol of a return to a holy state, especially took hold among Christians…” (pp 123-124)

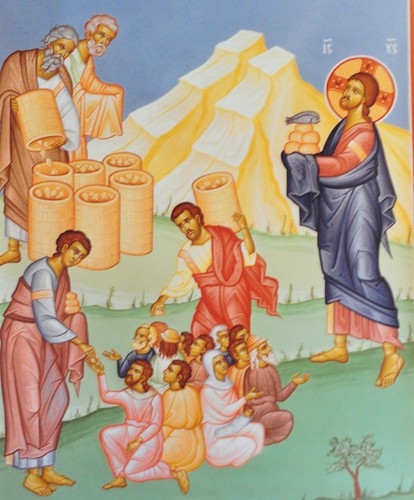

The desert – that place where you have to practice self-denial, abstinence and endurance just to survive – became for us a symbol of the sojourn to the Kingdom. However hard it may be, the journey is a blessed one because it does bring us to our destination – to Paradise, to the Kingdom of Heaven. And as God called Israel to the desert out of slavery to the great civilization of Egypt, so God calls us to Great Lent out of the civilized world, to that spiritual desert where we are not distracted by all the alluring things of the world and can concentrate on seeing God. In the desert we realize the need for God’s love and presence, we realize our survival depends upon God. We embrace the God of love, we pry ourselves away from the things that God has made so that we can fully embrace the Giver of the gifts. The absence of creaturely comforts reminds us there is a Creator of comforts and this God is far more important to us than all the things of the world. In going to the spiritual desert we acknowledge that we really can live without all of the luxuries of life in the civilized world.

Great Lent like the desert is “the quintessential zone of pilgrimage to the promised land.” The foods we eat during Great Lent remind us we are on a sojourn, and this world is a desert. The Israelites did not have wine in the desert because they had no time or place to establish vineyards. They were on the move, as we should be in our Lenten sojourn. They had no olive oil because they had no groves of olive trees in the desert and no means to press the olives to extract the oil. Wine and oil require the luxury of permanence, of being able to cultivate vineyards and orchards and of being able to process the produce from grapes to wine and from olives to oil. The fast is a harsh reminder of our reality – we are sojourners on earth. Yet, we come to realize how much we really love the things of this earth – meat, dairy, wine and oil – which we might desire more than we desire God the Giver of every good gift. Denying ourselves these things is to remind us we should desire God even more than we desire the blessings of His earth. We fast in order to experience the desire for these things so that we can then cultivate a desire for God even more than the things of the world that we so love. Fasting isn’t done because the things of the world are evil, but rather because we become addicted to them, treating them as our gods, acting as if we can’t live without them. Great Lent calls us to live for a time period on the Word of God.

Our own sojourn during Great Lent was foreshadowed by Israel’s sojourn through the desert after their escape from slavery in Egypt. Their own willingness to leave Egypt and head into the desert was done in the context of knowing that the desert was not a friendly, welcoming, nurturing place. The Israelites moved into the desert having learned from the Egyptians that the desert was the barren and lifeless wilderness controlled by the god Set. Set is one of the gods of Egypt, an evil one, brother to the god Osiris.

“Egypt is in many ways a seminal matrix for the desert experience. The desert of the Israelites is, of course, this desert, and the ways Egypt regarded it have some continuance in Israelite attitudes… Set, Osiris’ brother, is a force of disorder. He thus represents evil and hostility to humankind. … the evil Set, who is finally ousted from his sterile seizure of power, and exiled to the desert lands… Set, however, remains as a constant threat of disorder, destruction, and death; always prowling in the desert lands, never far away from the centers of civilized life which struggle to retain their fragile dominion over human existence. If an ancient went out into the desert he or she would risk the fearful encounter with daimones, the mid-level spiritual forces, sublunary deities, which the ancient world saw as ubiquitous powers. But in the desert these forces were habitually hostile and destructive: hungry servants of Set. … Set’s rule commenced when arid barrenness began and either killed all living things, or made them wild, murderously savage.

“Egypt is in many ways a seminal matrix for the desert experience. The desert of the Israelites is, of course, this desert, and the ways Egypt regarded it have some continuance in Israelite attitudes… Set, Osiris’ brother, is a force of disorder. He thus represents evil and hostility to humankind. … the evil Set, who is finally ousted from his sterile seizure of power, and exiled to the desert lands… Set, however, remains as a constant threat of disorder, destruction, and death; always prowling in the desert lands, never far away from the centers of civilized life which struggle to retain their fragile dominion over human existence. If an ancient went out into the desert he or she would risk the fearful encounter with daimones, the mid-level spiritual forces, sublunary deities, which the ancient world saw as ubiquitous powers. But in the desert these forces were habitually hostile and destructive: hungry servants of Set. … Set’s rule commenced when arid barrenness began and either killed all living things, or made them wild, murderously savage.

This notion of the fearfulness of the wilderness places forms an important backdrop to the classical appearance of the desert in Israel’s account of the escape from Egypt.” (p 125-126)

Israel walked out of civilized Egypt into Set’s desert. This helps us understand why Pharaoh was incredulous when Aaron and Moses requested permission from him to travel into the desert to worship their God. But Pharaoh said, “Who is the LORD, that I should heed his voice and let Israel go? I do not know the LORD, and moreover I will not let Israel go.“ (Exodus 5:2) Pharaoh knew the desert to be Set’s haunting place, why his slaves would want to leave civilization to honor an evil god was beyond his understanding. What Moses brings into Egypt in the plagues, Pharaoh will understand to be the destructive powers of Set. In the end Pharaoh expels the Israelites from Egypt realizing some divine power is present that he does not understand. Pharaoh sees himself as a god of the civilized world, but his kingdom is in chaos when in the presence of the God of Israel. Pharaoh never understood the Lord God as anything more than some manifestation of Set. And for the Israelites, the Lord God led them right into the haunts of Set, but in that very place the Egyptians did not want to go, God promised to reveal Himself.

Israel walked out of civilized Egypt into Set’s desert. This helps us understand why Pharaoh was incredulous when Aaron and Moses requested permission from him to travel into the desert to worship their God. But Pharaoh said, “Who is the LORD, that I should heed his voice and let Israel go? I do not know the LORD, and moreover I will not let Israel go.“ (Exodus 5:2) Pharaoh knew the desert to be Set’s haunting place, why his slaves would want to leave civilization to honor an evil god was beyond his understanding. What Moses brings into Egypt in the plagues, Pharaoh will understand to be the destructive powers of Set. In the end Pharaoh expels the Israelites from Egypt realizing some divine power is present that he does not understand. Pharaoh sees himself as a god of the civilized world, but his kingdom is in chaos when in the presence of the God of Israel. Pharaoh never understood the Lord God as anything more than some manifestation of Set. And for the Israelites, the Lord God led them right into the haunts of Set, but in that very place the Egyptians did not want to go, God promised to reveal Himself.

Next: Great Lent: Journeying into the Desert of Our Heart

“Two men went up into the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, ‘God, I thank thee that I am not like other men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week, I give tithes of all that I get.’ But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even lift up his eyes to heaven, but beat his breast, saying, ‘God, be merciful to me a sinner!’ I tell you, this man went down to his house justified rather than the other; for every one who exalts himself will be humbled, but he who humbles himself will be exalted.” (Luke 18:10-14)

“Two men went up into the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, ‘God, I thank thee that I am not like other men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week, I give tithes of all that I get.’ But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even lift up his eyes to heaven, but beat his breast, saying, ‘God, be merciful to me a sinner!’ I tell you, this man went down to his house justified rather than the other; for every one who exalts himself will be humbled, but he who humbles himself will be exalted.” (Luke 18:10-14)

This is the second and concluding post based upon my reading of John McGuckin’s “The Christian Sense of the Desert” in his book

This is the second and concluding post based upon my reading of John McGuckin’s “The Christian Sense of the Desert” in his book