Christians have in their long history experienced all sides of war – being attacked as well as sending forth armies to defend and protect themselves. The early Christian centuries saw Christians persecuted by the empire in which they resided: the Roman Empire brought to bear on the Christians all of the weight and might of its power to contain and eliminate them. At least as far as I know, the early Christians did not call their fellow Christians to strike back at the Empire in armed resistance. There were no calls to take revenge or to fight evil with evil, death with death, eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth.

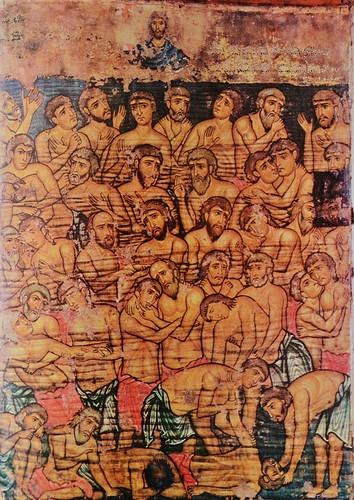

The persecuted Christians defended themselves through the writings and speeches of the apologists, such as St. Justin the Martyr. Despite seeing their fellow Christians martyred by the Empire, I’m not aware of any early Christian calling for or organizing an armed defense. Certainly they would have been aware of the armed rebellion by the Maccabees from the Scriptures. That was a Jewish example of how to respond to persecution – but the Christians didn’t follow that path. Miraculously, without an army or call to armed resistance, they survived and continued to gain new adherents. The witness of the martyrs and confessors continued to sew seeds in the hearts and minds of other Romans which yielded a harvest of faith in God among more and more of Rome’s denizens.

Only with the Emperor Constantine and the legends of his vision do we see an Empire being conquered by the cross with a use of force.

In later centuries, once the Empire itself embraced Christianity, the Christians found themselves with new moral dilemmas as to what it meant to be a Christian soldier and what it meant for Christians to go to war or to defend their empire. The Christians did not lose or forget the morality of the Gospel commands, but they struggled with how to apply it to their new found position of power. In the year 300, it was forbidden by the Empire for Christians to be in the army. By 400, it was required that to be in the Roman army you had to be a Christian.

One early Christian writer who did write about the moral dilemma for Christians being in the army and going to war is St. Augustine (d. 430AD). Apparently Augustine found that it was not war in itself which was wrong for Christians, but the motives and passions which guided the Christians which could be sinful.

“For Augustine, soldiers in battle must be motivated by charity, love of neighbor, and even love of enemies. They must not delight in the blood sport of war or be motivated by revenge.

‘The real evils in war are love of violence, revengeful cruelty, fierce and implacable enmity, wild resistance and the lust of power.’”

The moral problem as St. Augustine describes it is what war does to us internally. We can be changed by war so that we take some pleasure in the the violence we do against our enemies. We rejoice in their suffering and believe our wrath is godly. We come to find joy in destroying those that we have come to hate. It appears that for Augustine, the issue is losing the sense that we are defending the innocent and those who can’t protect themselves and coming to enjoy inflicting pain and suffering on those enemies we hate. It is dehumanizing ourselves and our enemies which itself is morally wrong. This is one of the evils of war – changing the very reason one goes to war and what one does in war into an evil. When war raises our own sinful passions and those passions take control of our behavior, then war causes evil to exist in us.

At first blush, Augustine seems hypocritical. He decries violence in the name of self-defense but allows killing in battle and says it is not murder. For Augustine, intention and authority are key. When an individual sheds blood with vengeance (motive) or without permission (authority), that person commits a sin; but as a tool or delegate of the state, the soldier can kill without sinning, so long as the soldier does so dispassionately (without taking delight) and in service to the common good.”

(Mark J. Allman, Who Would Jesus Kill?, p 169)

This is a very treacherous moral path. We can lose justification for our fighting in war if we allow sinful passions to take control of our reasoning. But it also is possible that leadership may have the authority to declare war and do it for wrong or evil intentions. The individual does not surrender responsibility for what he or she does to authority, but can without malice obey authority to serve others who cannot defend themselves. None of this glorifies killing, or makes war a good. The world is not perfect; it is fallen. It is in this world that we have to function and make choices – difficult and hard choices. We can make wrong choices, or right choices for wrong reasons, as well as wrong choices for right reasons. Whenever their is choice to be made, we answer ultimately to God’s judgment.

The question remains: What level of force is allowed to stop others from committing evil? When is lethal force morally correct?

The defense of war is that it is using lethal force to stop others from committing evil or from inflicting evil upon people. The moral dilemma remains for us: as people who are ourselves sinful and living in a fallen world, our motivations for doing things can be wrong. Our sinful passions can control our behaviors which can lead us to act for wrong reasons and to accomplish sinful ends. We can take men and women and remove from them moral reasoning and empower their sinful passions to commit acts of violence without having any remorse. The military has become quite successful at training its soldiers to accomplish their mission. That might be the key to military victory. But therein also lies part of the danger and evil of war. It is not only what we do to our enemies – it is what we do to ourselves that is the problem. In war we can encourage sinful passions to take control of ourselves. We can turn off our moral reasoning in order to accept or justify whatever behavior we engage in. We can dehumanize ourselves, not just our enemies, in order to win a war. But, as the Lord Jesus asks . . .

“what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world, and loses his own soul? Or what will a man give in exchange for his soul?” (Mark 8:36-37)

We can train soldiers to win wars, but we bear responsibility if they lose their souls in the process. Physical death may not be the worst end for the soldier. Those who die in battle are hailed as heroes. Those, however, who live and are emotionally and spiritually wounded, are sometimes pitied, sometimes forgotten, sometimes incarcerated, sometimes left homeless.

Certainly this tells us we have as a nation not only a responsibility to defend ourselves from evil, but we also have an obligation to tend to the men and women we send to war – to help them deal with their passions, moral dilemmas and regrets not only while in the military but when they return to civilian life. It is wrong to send young men and women to war, to make them killing machines and then to fail to help them return to society. The cost of war is not just supporting our military in the actual combat. It also means funding the care for the souls, hearts and minds of those who return from war with their moral, spiritual or emotional lives broken or in turmoil. The nation has a responsibility to rehumanize all who might have suffered because they went to war.

The cost of war and the evil of war can be the damage it does to us, to cause us to be less than human. The war may end, but sometimes it does not for those wounded by it.

Father Ted,

At first, your use of “we” seems clearly to speak of Christians. Then at the very end, the “we” seems to subtly shift to countrymen (Americans). Is there no distinction in these identities?

Should Christians favor Americans sending troops into battles that will involve them in combat with other nations where there are Christians who may be killed or injured?

–guy

Obviously there is a distinction – not all Americans are Christian and not all Christians are American! I have to wrestle with this issues both an a Christian and an American in as much as I live in two worlds.

Your 2nd question is another of the treacherous moral steps we have to deal with as Christians and as members of whatever nation we belong to.

As an Orthodox Christian it is very troubling to see Russians fighting Ukrainians or Russians fighting Georgians – both such battles pit Orthodox Christians vs. Orthodox Christian.

Christians need to think long and hard and pray long and hard before engaging in war against fellow Christians. But then we need to do that anytime we are part of a call to war.

Father Ted,

I am still fairly new in the faith, so please instruct me where I’m misunderstanding. While we are enjoined to love and serve everyone, surely we owe some greater debt of loyalty to fellow Christians, don’t we? i’m thinking here of St. Paul saying “Do good to all men, but especially to those of the household of faith.” i shouldn’t kill anyone, but i take it there is an ‘a fortiori’ sense in which i shouldn’t kill Christians.

My patron saint is Boris of Kiev who refused to resist his non-Christian brother’s assassins. If a fellow Christian really were convinced that he/she ought to kill me, shouldn’t i let it happen? i’m thinking here of where Paul said “Why not rather be wronged?”

–guy

Your first question reminds me of something St John Chrysostom once said with some exasperation – Jesus tells us to love our enemies but we don’t even love our friends to the level of being willing to give up everything for them.

The Gospel sets a very high moral bar which includes suffering wrong whether moral or not and suffering without taking revenge. Harder for us is what if it is others who suffer but not me? Do I have a duty to try to stop them from suffering?

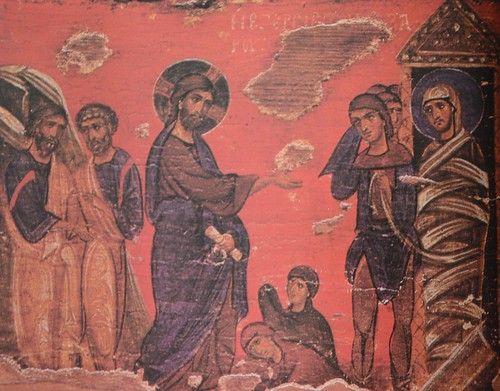

Jesus doesn’t totally address that issue. I can lay down my life for my friends. But does Christ ever expect us to use lethal force to defend friends or the defenseless?

Nice writeup. The truth is that war never really solves the issues they were meant to solve. The only people who benefit from wars are weapons contractors. Visit this link http://listernaija.com/2016/01/10-deadliest-world-events-in-human-history/ to see some of the wars with the highest death toll

Father Ted,

I’d like to think that the cross itself is an answer – maybe for all our sin and failing we can’t see it – but, in fact, it’s possible to defend the innocent, our friends, the defenseless, and also the guilty and our enemies, from themselves, from each other, from sin, death, and hell, all the while never inflicting damage on any of them, but only suffering ourselves. I’m not saying I know how to do that in every scenario. But I’d like to think the cross is exhibit A that for any given instance of war or violence, there’s a sense in which that’s not the best we could’ve done.

I think you have stated an ideal very well. It is very hard to life up to the ideal. But taking up the cross is possible in every situation.