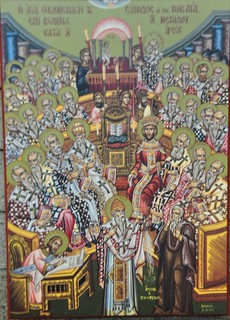

“It was with a spirit of reverential fear that the Fathers were then compelled to defend the divinity of the Son at the council of Nicea in AD 325. They sought to remind Christians that Christ’s coming into the world was a true manifestation of the eternal God and that his Incarnation opened the way to the fullness of salvation and of deification: ‘[God] was made man,’ said St. Athanasius, following St. Irenaeus, ‘that we might be made God.’ But such insistence on the eternal unity of the Father and the Son risked compromising or minimising the uniqueness, or irreducible specificity, of each of the divine persons. The Cappadocian Fathers worked in the course of the fourth century to formulate a theological language and to establish the meaning of precise terms that would permit Christians on one hand to distinguish the unity of the Three in essence, or shared substance, and, on the other, to express the mystery of each of the three persons by using the philosophical term ‘hypostasis.’ This term settled the trinitarian debate more conclusively than did the term ‘person,’ which had been introduced by Tertullian in the early third century, by emphasizing the unfathomable depth of personal being of each member of the Trinity.” (Boris Bobrinskoy, “God in Trinity,” The Cambridge Companion to Orthodox Christian Theology, p. 50)

“It was with a spirit of reverential fear that the Fathers were then compelled to defend the divinity of the Son at the council of Nicea in AD 325. They sought to remind Christians that Christ’s coming into the world was a true manifestation of the eternal God and that his Incarnation opened the way to the fullness of salvation and of deification: ‘[God] was made man,’ said St. Athanasius, following St. Irenaeus, ‘that we might be made God.’ But such insistence on the eternal unity of the Father and the Son risked compromising or minimising the uniqueness, or irreducible specificity, of each of the divine persons. The Cappadocian Fathers worked in the course of the fourth century to formulate a theological language and to establish the meaning of precise terms that would permit Christians on one hand to distinguish the unity of the Three in essence, or shared substance, and, on the other, to express the mystery of each of the three persons by using the philosophical term ‘hypostasis.’ This term settled the trinitarian debate more conclusively than did the term ‘person,’ which had been introduced by Tertullian in the early third century, by emphasizing the unfathomable depth of personal being of each member of the Trinity.” (Boris Bobrinskoy, “God in Trinity,” The Cambridge Companion to Orthodox Christian Theology, p. 50)