The Gospel Lesson for the 4th Sunday after Pascha comes from John 5:1-15.

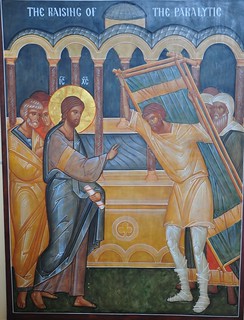

After this there was a feast of the Jews, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. Now there is in Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate a pool, in Hebrew called Bethzatha, which has five porticoes. In these lay a multitude of invalids, blind, lame, paralyzed. One man was there, who had been ill for thirty-eight years. When Jesus saw him and knew that he had been lying there a long time, he said to him, “Do you want to be healed?” The sick man answered him, “Sir, I have no man to put me into the pool when the water is troubled, and while I am going another steps down before me.” Jesus said to him, “Rise, take up your pallet, and walk.” And at once the man was healed, and he took up his pallet and walked. Now that day was the Sabbath. So the Jews said to the man who was cured, “It is the Sabbath, it is not lawful for you to carry your pallet.” But he answered them, “The man who healed me said to me, ‘Take up your pallet, and walk.'” They asked him, “Who is the man who said to you, ‘Take up your pallet, and walk’?” Now the man who had been healed did not know who it was, for Jesus had withdrawn, as there was a crowd in the place. Afterward, Jesus found him in the temple, and said to him, “See, you are well! Sin no more, that nothing worse befall you.” The man went away and told the Jews that it was Jesus who had healed him.

After this there was a feast of the Jews, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. Now there is in Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate a pool, in Hebrew called Bethzatha, which has five porticoes. In these lay a multitude of invalids, blind, lame, paralyzed. One man was there, who had been ill for thirty-eight years. When Jesus saw him and knew that he had been lying there a long time, he said to him, “Do you want to be healed?” The sick man answered him, “Sir, I have no man to put me into the pool when the water is troubled, and while I am going another steps down before me.” Jesus said to him, “Rise, take up your pallet, and walk.” And at once the man was healed, and he took up his pallet and walked. Now that day was the Sabbath. So the Jews said to the man who was cured, “It is the Sabbath, it is not lawful for you to carry your pallet.” But he answered them, “The man who healed me said to me, ‘Take up your pallet, and walk.'” They asked him, “Who is the man who said to you, ‘Take up your pallet, and walk’?” Now the man who had been healed did not know who it was, for Jesus had withdrawn, as there was a crowd in the place. Afterward, Jesus found him in the temple, and said to him, “See, you are well! Sin no more, that nothing worse befall you.” The man went away and told the Jews that it was Jesus who had healed him.

St. John Chrysostom (d. 407AD) says in a sermon:

“Having lately come across the incident of the paralytic who lay upon his bed beside the pool, we discovered a rich and large treasure, not be delving in the ground, but by diving into his heart: we found a treasure not containing silver and gold and precious stones, but endurance, and philosophy, and patience and much hope towards God, which is more valuable than any kind of jewel or source of wealth.” (Christ’s Power to Heal: The Paralytic, p 2)

Chrysostom like many of the fathers praises the paralytic for his patient persevering in the face of prolonged suffering. Perhaps it is true at that time that there were actually few cures for diseases and patiently enduring suffering was seen as heroic and godly since there was no alternative. It is more difficult for us today to be patient in the face of suffering as we want immediate cures or at least instant relief from suffering and we don’t appreciate the Stoicism embraced by the ancient Christians that a man of perfection is already beyond caring about pleasure or pain.

Fr. John Breck in his writing offers a more biblical view which makes more sense to the modern Christian that suffering is not to be denied or ignored but that it might in itself have some redeeming value.

“Suffering can make us aware of our total dependence on the inexhaustible love and mercy of God. Like no other experience known to us, it focuses our attention on our weakness and vulnerability, and on God as the unique source of mercy, grace and ultimate healing. As a corollary, suffering can bring a heightened self-consciousness and, with it, an awareness of our personal limitations. More than perhaps any other experience, pain and suffering signal the fact that we are not in control. This is a profoundly humbling experience, one that can lead to either despair or to previously unknown heights of faith and hope. Suffering can also have the effect of purging and purifying the passions, that is, the desires and deceptions that corrupt our relationship with God, with others, and with ourselves. At the same time, it draws our attention to the present moment, forces us to reorder our priorities, and invites us to seek above all ‘the one thing needful’ (Luke 10:42). Suffering also brings awareness to our mortality. In Christian monastic tradition, the monk rises to pray with the admonition, ‘Remember death!” There is nothing morbid about the memory of death. Rather, it is a joyful expression of hope, based on the conviction that by his death, Christ has once and for all destroyed the power of death. Suffering can also foster ecclesial communal ties with others on whom we depend. In return, their own spiritual growth can be enhanced by the experience of sharing another’s pain through their prayer and gestures of care. Finally, suffering offers the possibility to share in the life and saving mission of the crucified and risen Lord. For the dying patient, this means to take up one’s cross and to follow Christ to his own passion and death. To endure one’s suffering for the sake of Christ, in the certainty that one will rise with him into the fullness of life, is also to offer to others the most eloquent and effective witness or martyria possible.” (The Sacred Gift of Life, p 216)

“Suffering can make us aware of our total dependence on the inexhaustible love and mercy of God. Like no other experience known to us, it focuses our attention on our weakness and vulnerability, and on God as the unique source of mercy, grace and ultimate healing. As a corollary, suffering can bring a heightened self-consciousness and, with it, an awareness of our personal limitations. More than perhaps any other experience, pain and suffering signal the fact that we are not in control. This is a profoundly humbling experience, one that can lead to either despair or to previously unknown heights of faith and hope. Suffering can also have the effect of purging and purifying the passions, that is, the desires and deceptions that corrupt our relationship with God, with others, and with ourselves. At the same time, it draws our attention to the present moment, forces us to reorder our priorities, and invites us to seek above all ‘the one thing needful’ (Luke 10:42). Suffering also brings awareness to our mortality. In Christian monastic tradition, the monk rises to pray with the admonition, ‘Remember death!” There is nothing morbid about the memory of death. Rather, it is a joyful expression of hope, based on the conviction that by his death, Christ has once and for all destroyed the power of death. Suffering can also foster ecclesial communal ties with others on whom we depend. In return, their own spiritual growth can be enhanced by the experience of sharing another’s pain through their prayer and gestures of care. Finally, suffering offers the possibility to share in the life and saving mission of the crucified and risen Lord. For the dying patient, this means to take up one’s cross and to follow Christ to his own passion and death. To endure one’s suffering for the sake of Christ, in the certainty that one will rise with him into the fullness of life, is also to offer to others the most eloquent and effective witness or martyria possible.” (The Sacred Gift of Life, p 216)

Fr. Ted:

I always think of the example my mother set and since tomorrow is Mother’s Day, I thought sharing this story would be appropriate. My mother had Multiple Sclerosis. She endured a chronically progressive disease that resulted in broken hips on both sides, pinning procedures, and eventually replacement of both hips. Eventually, she became quadriplegic and could not even feed herself. My father cared for her until she died.

Mom set the example of redemptive suffering for others around her. At her funeral, several people told me how faithful she was to Jesus Christ even in the face of such a debilitating disease. She never complained publicly or griped about it. I heard complaints at home, after all she is a human being. Nevertheless, her public demeanor was always calm and silent. She accepted her condition.

I have a cousin who is a Roman Catholic priest who told me that he never met a woman who came closer to the Blessed Virgin Mary than my mother. It was no accident that she was named Dolores. She was, indeed, a “Mother of Sorrows.”

Val

Thanks for sharing the wonderfully inspiring witness of your mom.

You are welcome, Fr. Ted.