This is the 15th blog in this series which began with the blog Being and Becoming Human. The previous blog is Angel and Animal; Spiritual and Physical.

This is the 15th blog in this series which began with the blog Being and Becoming Human. The previous blog is Angel and Animal; Spiritual and Physical.

In this blog we will look specifically at three excerpts from the writings of St. John Chrysostom (d. 407AD) related to humans having both an animal nature and also having a spiritual nature. St. John is ever the moralist, and he unfavorably relates the animal nature in humans to our failure to behave in a human manner.

“I repeat, and shall not cease saying it: come in, prove yourself human lest you give the lie to your natural title. Do you understand what is said to you? He is a human being, someone may say, but a human being often in name only, not a human being in his way of thinking.

I mean, when I see you living an irrational life, how am I to call you a human being and not an ox? When I see you robbing others, how am I to call you a human being and not a wolf? When I see you committing fornication, how am I to call you a human being and not a swine? When I see you being fraudulent, how am I to call you a human being and not a serpent? When I see you with venom, how am I to call you a human being and not a snake? When I see you being a fool, how am I to call you a human being and not an ass? When I see you committing adultery, how am I to call you a human being and not a lusty stallion? When I see you disobedient and forward, how am I to call you a human being and not a stone? . . .

I mean, when I see you living an irrational life, how am I to call you a human being and not an ox? When I see you robbing others, how am I to call you a human being and not a wolf? When I see you committing fornication, how am I to call you a human being and not a swine? When I see you being fraudulent, how am I to call you a human being and not a serpent? When I see you with venom, how am I to call you a human being and not a snake? When I see you being a fool, how am I to call you a human being and not an ass? When I see you committing adultery, how am I to call you a human being and not a lusty stallion? When I see you disobedient and forward, how am I to call you a human being and not a stone? . . .

How, do you ask, am I to become a human being? If you keep the thoughts of the flesh under control, those brutish thoughts, if you expel lewd habits, if you expel an inopportune desire for money, if you expel that wicked tyrant, if you make your own place pure. But how do you become a human being? By coming here where human beings are created. If I receive you as a stallion, I turn you into a human being; if I receive you as a wolf, I turn you into a human being; if I receive you as a serpent, I turn you into a human being, not changing your nature but transforming your free will.” (St. John Chrysostom, OLD TESTAMENT HOMILIES Vol 3, pp 87-88)

Chrysostom frequently compares sins to the behavior of a variety of animals. He sees repentance as turning away from behaving purely according to our animal nature by mindfully gaining control of our passions and appetites. Then in the Church through baptism those who live according to animal nature are transformed into human beings who live by reason (rapacious wolves are transformed into reason-endowed sheep!). Reason is God’s gift to humans which distinguishes us from all other animals.

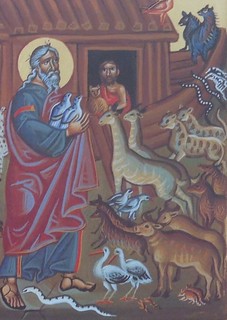

Chrysostom does not miss a chance to moralize. Seeing the simple statement of Genesis 6:9, “Noah was a righteous man” (Greek: anthropos: meaning a human being, rather than a male), Chrysostom sees opportunity to wax eloquently on what it is to be human. And perhaps, since Noah, according to the biblical story, led a pair of each of the animals in the world into the ark, Chrysostom found an excellent example of a human who differed from all the other animals. Noah is a human who can be contrasted with all other animals since he was called to lead them all (Genesis 6:9-22) thus fulfilling God’s original intention for human beings (Genesis 1:26-28). Noah is the only human in the Old Testament who actually exhibits dominion over all of the animals on earth, and the animals actually obey his lead (Genesis 7:8-9). The animals follow Noah in an orderly fashion into the ark as if they are in a liturgical procession. Chrysostom’s view is that Noah in his day is really the only true human being left on the planet, all others being dehumanized through sin were thus inhuman, mere animals bereft of the glory of God which they originally possessed.

Chrysostom does not miss a chance to moralize. Seeing the simple statement of Genesis 6:9, “Noah was a righteous man” (Greek: anthropos: meaning a human being, rather than a male), Chrysostom sees opportunity to wax eloquently on what it is to be human. And perhaps, since Noah, according to the biblical story, led a pair of each of the animals in the world into the ark, Chrysostom found an excellent example of a human who differed from all the other animals. Noah is a human who can be contrasted with all other animals since he was called to lead them all (Genesis 6:9-22) thus fulfilling God’s original intention for human beings (Genesis 1:26-28). Noah is the only human in the Old Testament who actually exhibits dominion over all of the animals on earth, and the animals actually obey his lead (Genesis 7:8-9). The animals follow Noah in an orderly fashion into the ark as if they are in a liturgical procession. Chrysostom’s view is that Noah in his day is really the only true human being left on the planet, all others being dehumanized through sin were thus inhuman, mere animals bereft of the glory of God which they originally possessed.

“’Noe,’ it says, ‘was a man.’ . . . You see, since the other people had lost the status of human beings through falling into the pleasures of the flesh, this man (Scripture says) retained the character of a human alone among such a vast multitude. This, after all, is when a man become human, when he practices virtue: it is not having the appearance of a human being—eyes, nose, mouth, cheeks and other features—that establishes the human being: these, in fact, are parts of the body. I mean, we would call a human being the man who retains the character of a human being. But what is the character of a human being? Being rational. Why so? Someone will say, “Weren’t those others rational also?” Still, it is not merely this attribute, but also being virtuous and avoiding evil and getting the better of improper passions, following the Lord’s commands—this is what makes a human being.

For proof that Scripture’s habit is not to bestow the title of human being on those who practice evil and neglect virtue, listen to the words of God, as we were saying yesterday, ‘My spirit is not to remain with these human beings on account of their being carnal; [Genesis 6:3]’ in other words, he is saying, I regaled these people with a being constituted of flesh and spirit; but as though composed of flesh only, they thus neglect virtue in a spiritual manner and have now proved to belong completely to the flesh. . .

Do you see how Holy Scripture knows how to call human only the person practicing virtue and doesn’t think the others are human, calling them instead flesh at one time and earth at another? Hence at this place, too, in promising to list the genealogy of the good man it says, ‘Noe was a human being.’ You see, he alone was a human being, whereas the others weren’t human beings; instead, while having the appearance of human beings they had forfeited the nobility of their kind by the evil of their intention, and instead of being human they reverted to the irrationality of wild animals. . . .

Do you see which people Sacred Scripture is prepared to call human beings? Hence, when even from the outset the Creator of all saw the creature he had made, he said, ‘Let us make a human being in our image and likeness’ – that is to say, to have control both of all visible things and the passions arising within him; to have control, not to be controlled. If, however, they forfeit this control and would rather be controlled that have control, they lose also their human status and change their name to that of wild animals.” (St. John Chrysostom, HOMILIES ON GENESIS 18-45, pp 95, 96, 98)

For St. John Chrysostom to live only to satisfy one’s carnal desires is to give up being a human person. To rationally control one’s desires, passions and appetites is to use the rationality/reason with which God had gifted human beings from the beginning – the very thing which differentiates us from other animals. If we don’t want to live by reason, if we don’t want to live according to the image and likeness of the Creator, then we choose to live like the other animals on earth which lack reason.

For St. John Chrysostom to live only to satisfy one’s carnal desires is to give up being a human person. To rationally control one’s desires, passions and appetites is to use the rationality/reason with which God had gifted human beings from the beginning – the very thing which differentiates us from other animals. If we don’t want to live by reason, if we don’t want to live according to the image and likeness of the Creator, then we choose to live like the other animals on earth which lack reason.

It is exactly from humans who live according to their animal nature that we need protection. More dangerous to us than any venomous animal, more detrimental to us and more deadly is the human who has forsaken God-given reason/rationality and who like an animal uncontrollably follows its genetically determined impulses. So Chrysostom sees the Psalmist asking God not to deliver him not from dangerous, vicious animals, but from people who have become inhuman.

“Rescue me, Lord, from an evil person; from an unrighteous man deliver me (Psalm 140:1) Where now are those who ask, ‘What is the purpose of wild beasts? Of scorpions? What purpose do they have?’ I mean, look: a living creature is found to be betraying signs of worse evil, not from nature but from disposition – the human being. This is the reason, to be sure, that the inspired author omits mention of those other creatures and asks to be delivered from this one. Why on earth? I ask: to suggest that, since it is like that, human beings should not be created? But to say this is an index of extreme folly: nothing is harmful about the human being except sin; with that disposed of, everything is trouble-free, easy, peaceful – just as, consequently, with that present, everything becomes crags and tempests and shipwrecks. Now, let no one condemn us for saying a human being in the grip of vice is more vicious than a wild beast. I mean, the latter, even if not gentle by nature, can easily be deceived, and what you see is what you get, whereas the human being who contemplates wickedness adopts many guises and is more difficult to ward off than an animal, often proving to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Hence, too, many people incautiously fall victim to such types. Since, then, such creatures are difficult to detect, the inspired author turns to prayer and calls on help from God to be freed from such wiles.” (St. John Chrysostom, COMMENTARY ON THE PSALMS Vol 2, p 264)

As the folk story has it, scorpions will be scorpions – they can’t help behaving according to their natures. Humans on the other hand are capable of denying the self for the good of others. Humans can practice self-control, can repent and can forgive.

Pingback: Angel and Animal; Spiritual and Physical | Fr. Ted's Blog

Thanks for this piece on Blessed John. I found it helpful.

Pingback: The Human Being: A Spiritual Animal | Fr. Ted's Blog