This is the 17th blog in this series which began with the blog Being and Becoming Human. The previous blog is The Human Being: A Spiritual Animal. With this blog we will conclude our look at the human as being an animal as well as being spiritual. I will remind the readers, that this blog series is offering a collection of quotes that I came across in a life time of reading which are related to the theme of being and becoming human. The blog series is not a research paper, but truly a collection of quotes which I have brought together as I continue to reflect on this topic.

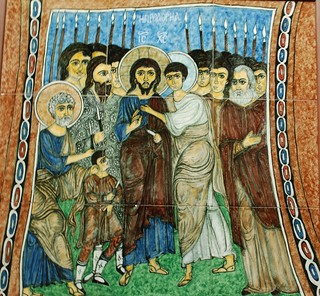

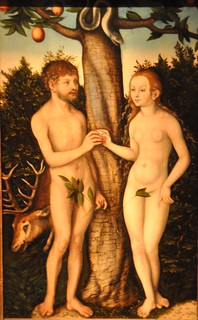

“Man is a mystery. We carry within us an age-old inheritance – all the good and precious experience of the prophets, the saints, the martyrs, the apostles and above all of our Lord Jesus Christ; but we also carry within us the inheritance of the evil that exists in the world from Adam until the present. All this is within us, instincts and everything, and all demand satisfaction. If we don’t satisfy them, they will take revenge at some time, unless, that is, we divert them elsewhere, to something higher, to God.

“Man is a mystery. We carry within us an age-old inheritance – all the good and precious experience of the prophets, the saints, the martyrs, the apostles and above all of our Lord Jesus Christ; but we also carry within us the inheritance of the evil that exists in the world from Adam until the present. All this is within us, instincts and everything, and all demand satisfaction. If we don’t satisfy them, they will take revenge at some time, unless, that is, we divert them elsewhere, to something higher, to God.

That is why we must die to our ancestral humanity and enrobe ourselves in the new humanity. This is what we confess in the sacrament of baptism.” (Elder Porphyrios, WOUNDED BY LOVE, p 134)

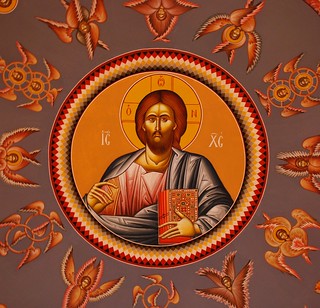

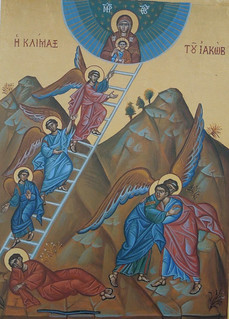

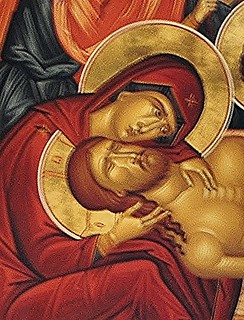

In speaking about “our ancestral humanity”, Saint Porphyrios is describing humanity bereft of union with God, in other words, fallen humanity. Despite being fallen creatures and living in the world of the Fall, we humans still and always have an innate connection with God. We are created in God’s image and likeness,and we breathe God’s holy breath. Despite the Fall, we still have the potential to be so much more than merely ancestral humanity – theosis is a possibility for us. We can aspire to something beyond our animal nature.

“Everyone must bear in mind that every man possesses, besides his animal nature, a spiritual nature also; that as the animal nature has it requirements, the spiritual one has its own requirements too. The requirements of the animal nature are: drink, food, sleep, breath, light, clothing, warmth; whilst those of the spiritual nature are meditation, feeling, speaking, communion with God through prayer, Divine Service, the sacraments, instruction in the Word of God, and fellowship with our neighbor through mutual conversation, charitable help, mutual instruction and teaching. We must also bear in mind that our animal nature is temporal, transitory, perishable, whilst the spiritual one is eternal, not transitory and indestructible; that we must despise the flesh as perishable, and care for the soul, which is immortal, for its salvation, its enlightenment, its cleansing from sins, passions, and vices from its adornment with such virtues as meekness, humility, gentleness, courage, patience, submission, and obedience to God and men, purity and abstinence.” (St. John of Kronstadt, MY LIFE IN CHRIST Part 1, p 244)

If we live only to care for our animal desires and instincts, we will live as animals. If however we aspire for that divine life beyond our animal nature, God blesses that desire and unites us to divinity. The Christian life consists in living in such a way as to care more for our relationship with God than with our animal nature, to nurture the soul, not just the body. Our goal is not to abandon the body but to unite the body to God, to be God’s temple, to partake of the divine nature.

“How strange it is! I, a Christian, a heavenly man, am occupied with everything earthly, and care but little for heavenly things. I am transplanted in Christ into heaven, but meanwhile I cling with all my heart to earth, and apparently would never desire to be in heaven, but would prefer to always remain on earth, although earthly things, notwithstanding their delights, oppress and torment me; although I see that everything earthly is uncertain, corruptible, and soon passes away; although I know, and feel that nothing earthly can satisfy my spirit, can appease and rejoice my heart, which is constantly disturbed and grieved by earthly vanity. How long, therefore, shall I, a heavenly man remain earthly?” (St. John of Kronstadt, MY LIFE IN CHRIST Part 2, p 9-10)

“How strange it is! I, a Christian, a heavenly man, am occupied with everything earthly, and care but little for heavenly things. I am transplanted in Christ into heaven, but meanwhile I cling with all my heart to earth, and apparently would never desire to be in heaven, but would prefer to always remain on earth, although earthly things, notwithstanding their delights, oppress and torment me; although I see that everything earthly is uncertain, corruptible, and soon passes away; although I know, and feel that nothing earthly can satisfy my spirit, can appease and rejoice my heart, which is constantly disturbed and grieved by earthly vanity. How long, therefore, shall I, a heavenly man remain earthly?” (St. John of Kronstadt, MY LIFE IN CHRIST Part 2, p 9-10)

We remain merely earthly, as long as we live only according to our animal nature, the flesh. We are however more than our bodies. As the mind is more than the brain, so the self is more than a body. It is our ability to aspire for the divine life that gives sanctity to human life. We value the unborn as well as the aged because each is loved by God.

“Who utterly low and brutish is the level to which a human mind has to sink before it can look at an old lady in a nursing home bed suffering some incurable disease and call this life and this suffering ‘meaningless’, lacking in ‘quality of life’. To call this the ‘quality of life ethic’ is like calling a cannibal a chef.

If this sneeringly snobbish judgment is true of the old lady, it is true a fortiori of Christ. If her cross of suffering, her deathbed, lacks ‘quality’, then his Cross and death-tree also lack ‘quality’.

‘Quality’ is thus used as a professional euphemism for sex and money. “ (Peter Kreeft, Christianity for Modern Pagans, p 58)

Human life is not measured purely in a utilitarian fashion, for what a person can produce, or consume. Human life is measured only by the Creator God’s love for each of us. God bestows upon us a life which is more than our bodies. The human is not completely defined by his or her physical existence, nor is a human life coterminous with its body. Each human being is not only body but also spiritual. Roman Catholic Professor Peter Kreeft offers the following analogy of the difference between a driver and the car to explain the relationship of a person (soul) to the body.

“Here is empirical proof of our doubleness, proof of an immaterial and thus immortal soul, and refutation of materialism. It is a fact that wise men are not driven by their animal passions as a car is driven by a driver; but they control them. They are the drivers. The materialist wants us to believe that the body is a car that drives itself, or that the driver is just another one of the parts of the engine; that the mind is merely the brain. How absurd! How could a mere machine negate its own drives and overcome its passions? Only a double being can oppose itself—something like a ‘thinking reed’. A cannot oppose A. Only A in AB can oppose B in AB.” (Christianity for Modern Pagans, p 59)

“Here is empirical proof of our doubleness, proof of an immaterial and thus immortal soul, and refutation of materialism. It is a fact that wise men are not driven by their animal passions as a car is driven by a driver; but they control them. They are the drivers. The materialist wants us to believe that the body is a car that drives itself, or that the driver is just another one of the parts of the engine; that the mind is merely the brain. How absurd! How could a mere machine negate its own drives and overcome its passions? Only a double being can oppose itself—something like a ‘thinking reed’. A cannot oppose A. Only A in AB can oppose B in AB.” (Christianity for Modern Pagans, p 59)

Professor Kreeft continues with his criticism of materialism:

“We are metaphysically very good because we are created in the image of the absolutely good God. But we are morally very bad because we have despised our Creator. Modern paganism says we are not metaphysically very good at all, because we are merely trousered apes; and not morally very bad at all because there is no divine law to judge us as very bad. There is only man-made societal law, that is, our own pagan society’s expectations, and these are quite low, negotiable and revisable. ‘Here, kid. Take a condom. We know you’re incapable of free choice and self-control. We expect you to play Russian roulette with AIDS, so we’re giving you a gun with twelve chambers instead of six.” (Peter Kreeft, Christianity for Modern Pagans, p 62)

We are not merely bodies, nor do we have bodies over which we have no control. We are capable of exercising control over our bodies, as our bodies are not separate from our minds, hearts or souls. We are a whole being with free will, conscious awareness and consciences. We are normally and naturally able to exert control over our bodies, desires and thoughts. Thought it is obvious in the world that some will not control themselves, and some due to the fall have lost the ability to control themselves. This is not natural to humans, but is part of our struggle of living in the world of the Fall.

“Thus our love of pleasure took its beginning from our likeness to the irrational creation, but was increased by human transgressions, begetting such a variety of sinning flowing from pleasure, as is not to be found among the animals. Thus the rising of anger is indeed akin to the impulse of the animals, but it is increased by the alliance with our processes of thought. For thence come resentment, envy, deceit, conspiracy, hypocrisy: all these are the result of the evil husbandry of the intellect. For if the passion is stripped of this alliance with the processes of thought, the anger that is left behind is short-lived and feeble – like a bubble, bursting as soon as it comes into being.” (Andrew Louth , Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology), Kindle Loc. 1496-1501)

“Thus our love of pleasure took its beginning from our likeness to the irrational creation, but was increased by human transgressions, begetting such a variety of sinning flowing from pleasure, as is not to be found among the animals. Thus the rising of anger is indeed akin to the impulse of the animals, but it is increased by the alliance with our processes of thought. For thence come resentment, envy, deceit, conspiracy, hypocrisy: all these are the result of the evil husbandry of the intellect. For if the passion is stripped of this alliance with the processes of thought, the anger that is left behind is short-lived and feeble – like a bubble, bursting as soon as it comes into being.” (Andrew Louth , Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology), Kindle Loc. 1496-1501)

As stated earlier in this blog series, humans can be more damaging and dangerous than any wild animal for we can use our intellects, wills and desires to choose evil. God become human in Jesus Christ in order to show us how to be human so that we can become like God.

“‘What good will it do a man if he gains the whole world but loses his soul?’

“‘What good will it do a man if he gains the whole world but loses his soul?’ “When we read in the writings of the

“When we read in the writings of the