This is the 4th blog in this series considering the book BAD RELIGION: HOW WE BECAME A NATION OF HERETICS by Ross Douthat. The first blog is A Recent History of American Heresy. The previous blog is Some More American Heresies.

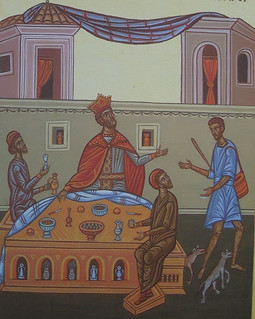

Perhaps the most obvious arena in which American Christians have had a different attitude than Christians historically have had is in relation to wealth. Christ, the itinerant preacher, Himself lived a rather impoverished life and never pursued wealth. He taught that one cannot serve God and mammon (Matthew 6:19-34; Luke 16:13-31). The New Testament has several warnings and woes for those who are rich or who pursue wealth (for examples, see Luke 6:20-25; 1 Timothy 6:9-10; James 1:10-11). And the Epistle of James portrays the rich as those who persecute the Christians and who face a wrathful judgment from God (James 2:6-7; 5:1-6).

Perhaps the most obvious arena in which American Christians have had a different attitude than Christians historically have had is in relation to wealth. Christ, the itinerant preacher, Himself lived a rather impoverished life and never pursued wealth. He taught that one cannot serve God and mammon (Matthew 6:19-34; Luke 16:13-31). The New Testament has several warnings and woes for those who are rich or who pursue wealth (for examples, see Luke 6:20-25; 1 Timothy 6:9-10; James 1:10-11). And the Epistle of James portrays the rich as those who persecute the Christians and who face a wrathful judgment from God (James 2:6-7; 5:1-6).

Some may argue that the New Testament’s negative attitude toward wealth may have something to do with how unevenly it was distributed in the ancient world and how those with wealth may have persecuted the Christians. America, on the other hand, they might argue, has been committed to a broader distribution of wealth (even if it only trickles down!). America has economically grown because of its banking policies including its lending policies and has created a middle class who share in the benefits of the country’s wealth. As a nation America has none of the reservations about wealth that we find in the authors of the New Testament.

Douthat in his book describes one of the most prominent heresies active in American religion today as the “prosperity Gospel”, the theology of “God and Mammon” which says you don’t have to choose between the two masters, but can in fact serve them both (or perhaps in American thinking, make them both serve you!). America has embraced completely prosperity as a sign of God’s blessings and has ignored almost completely sins and temptations that the Bible associates with wealth including greed and idolatry (Colossians 3:5) and that prosperity (Mammon) is competing with God for out loyalty.

“The prosperity gospel … is a message that’s tailored less to the very rich than to the middle and working classes—to people who are hardworking but financially insecure, who feel that they have to think about money all the time because they’re trying to make more of it, and who want to be reassured that their striving is in accordance with God’s plan rather than a threat to their salvation. … is just as likely to involve ministers who prosper by flattering their upwardly mobile, American Dreaming congregations, telling them to keep on striving and praying, because God wants them to keep up with the Joneses next door.” (p 190)

While indeed wealth can be a blessing, it can also be a temptation, and it is possible for a man to lose his soul and gain the world (Luke 9:23-27; Matthew 16:24-26; Mark 8:34-38). Wealth comes for Christians with both spiritual risk and responsibility. The American Christian embrace of wealth is often completely uncritical and seems to assume wealth can only be a good. Americans can be very thankful for their prosperity, but when wealth is governed by selfish, self-centered behavior it becomes wanton and destructive.

“This is where the union of God and Mammon goes astray, ultimately: it succumbs to a naiveté about how riches are often accumulated and about the dark pull that money can exert over the human heart. And its sunny boosterism leads believers into temptation, equipping them for success without preparing them for setbacks—which in turn makes failure all the more devastating when it finally, inevitably arrives.” (p 207)

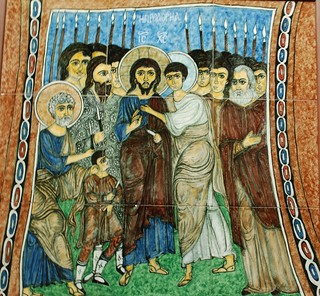

Whereas in early Christianity, greed was one of the seven deadly sins, in America greed is often glossed over or given more euphemistic titles of blessings, prosperity and wealth. Greed was seen as a deadly passion in Orthodox writings, but it becomes fashionable and desirable in American spiritual parlance. For Americans there seems to be little sense that enough is enough. And certainly wealth does not automatically produce virtue in anybody. Rather, wealth is no cure for greed, and can lead to jealousy, fear, hyper-vigilance and making self-preservation at all costs to be the greatest virtue. In Orthodox Holy Week hymns it is the betrayer Judas Iscariot who is said to be a lover of money. He is the poster child for the notion that you cannot serve God and Mammon.

Douthat also sees the embrace of wealth by Christians to have another temptation: the idea that wealth can solve all the world’s problems. This he suspects is what happens to liberal Christianity’s embrace of taxes and big government: money leads to utopian ideals.

“But like many forms of liberal Christianity, the marriage of God and Mammon half-expects somehow to undo the Fall, through the beneficence of Providence and the magic of the free market. In its emphasis on the virtues of prosperity, it risks losing something essential to Christianity—skipping on to Easter, you might say, without lingering at the foot of the cross. . . . Christianity risks becoming an appendage to Americanism—a useful metaphysical thread for a capitalist society’s social fabric, but a faith that’s bound, perhaps fatally to the rise and fall of the gross domestic product.” (p 205)

Wealth does come with some blessings. Christians welcomed the blessings as they turned to building churches and engaging in mission and ministry throughout the world. Douthat’s concern is that prosperity can blind us to its temptations and even to understanding what is important, for fund raising can become a goal in itself by which we measure the success of the Church. Yet Christ never established fund raising as a measure of Christian success.

“[The prosperity Gospel] is particularly well suited to successful church-building, where it translated into what the sociologist Michael Hamilton has memorably described as a theology of ‘more money, more ministry.’ … but from post-World War II era onward…. a more entrepreneurial approach. As Hamilton writes, ‘leaders of evangelical organizations scrambled to lay claim to as much of the new American wealth as they could’ – not for their own enrichment (or not always), but for the sake of spreading the Gospel.” (p 197)

The Church thus becomes more and more shaped by the methods, structures and models of American business, and becomes measured by those same standards as well. Success becomes numbers and especially financial success becomes the sole measure of whether God is blessing something.

“The one who pursues money will be led astray by it.” (Sirach 31:5)

There is much wisdom in the adage that says, “Money is a good servant but a bad master.” I interpret Douthat to be wondering aloud whether money is the servant or has become the master in much of American religion especially in those involved in the media market.

Douthat expresses another concern:

“… the marriage of god and Mammon is nothing more than Social Darwinism with a religious face.” (p 203)

Survival of the fittest in the religious world: those survive that have or can obtain money. ‘Thems that have, get more.’ ‘The oppressed are also to blame for their own condition.’ But in that formula, where is Christ the impoverished preacher of Galilee and where is the Gospel which calls us to deny ourselves in order to follow Christ?

Then Jesus said to them, “Whose head is this, and whose title?”

They answered, “The emperor’s.”

Jesus said to them, “Give to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” (Mark 12:16-17)

Pingback: Some More American Heresies | Fr. Ted's Blog

Father Ted,

i’ve been watching a BBC documentary on the 19th century British workhouses, and it’s brought to mind another feature of bad ideas about wealth that many Christians have adopted–namely, that levels of wealth are necessarily indicative of virtue or vice. In other words, if someone is particularly wealthy, it can only be because he’s doing good and right things: he must have a good work ethic, be responsible, shrewd and wise, etc. And if someone is poor, it can only be because he’s doing things wrong and bad: he must be irresponsible, lazy, unruly, shameless, etc. Poverty was quite literally a crime, and the workhouses were ultimately designed to shame or punish the poor. The problem was thought to be the lack of virtue on the part of the poor. Perhaps if the poor could be sufficiently humiliated, they would be shamed into reforming their lives. Once they reformed their lives, then certainly they’d get some money and hang on to it. And so the more “undeserving” of help the state judged certain impoverished persons to be, the more it shamed and punished them as it helped.

i don’t think we’ve got rid of this Victorian mentality. Our notion that i have money because i earned it, and others are poor because of their own fault seems to me to be a systemic way in which we’ve allowed ourselves to attempt to “serve both God and mammon.”

That wealth is a sign of God’s favor has been a common thought even from the pages of the Old Testament. In the Gospel lesson of the rich young man talking to Christ and he asks Christ “what do I still lack?”, Christ’s answer – give away all your wealth and come follow me – is very troubling to a person who believes that their wealth is the very sign that God favors them, approves of them and blesses them for how good they are.

Interesting that the Patristic Fathers say poverty is no crime and no shame. It is not a vice, nor is wealth a virtue. The poor can be as greedy as the rich, and the rich can be as spiritually impoverished as the poor. It is our hearts that get judged by God, not what we own. A rich man and a poor man can both be virtuous or riddled with vices, but they are judged by what they do with what they have.

And the Fathers tended to see wealth not as something earned, nor even as a gift from God to some favored ones, but more a loan from God which becomes a stewardship for us and we will have to give an account for what we do with what God has lent to us. Some of the desert Fathers thought the worst words in our speech were “my” and “mine.”

Pingback: Narcissism and the God Within | Fr. Ted's Blog